Pictures Will Tell You More

Right, in a tent in Sumatra, a geological crew examines maps.

Right, this surveyor, knee deep in swamp water, is trying to determine the exact course of a river in Leopard Bayou, Louisiana, U.S.A. Above, a map maker (called a cartographer) is at work in the Sahara desert. Aerial photographs are also studied for signs of changes in the general lay of the land, and for certain kinds of trees and bushes that would suggest to the trained eye differences in the underlying rocks. Exploring for Petroleum

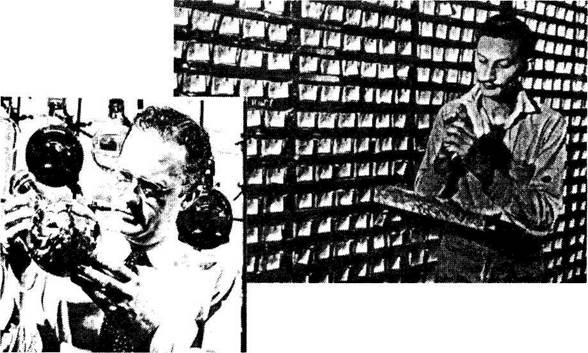

rock called strata, that crop out from the soil. They find clues in canyons and gullies. They try to "read" rock layers. They study the fossils (petrified animal life) imbedded in rock. The Canadian geologist, above, is doing a chemical test on a rock chip; and the man at right has just been landed by helicopter in a remote part of the desert. Here, he will gather up rock samples. Geologists study the shape of the hills, mountains, and rocks on top of the earth for clues as to where to find oil traps. They also look for outcrops, formations of

Chapter Two

Oilmen explore steaming jungles, waterless deserts, and frozen wastes. They hack a way through almost impassable bush. They carry their machinery up steep mountainsides, and through swamps like the one at right in Louisiana, U.S.A.

They wade through marshes, build roads through forests, and send all kinds of instruments, including themselves, down into the depths of the seas. The testing instrument above is being lowered into the water at Victoria, Australia. A diver starts into the sea by way of a steel ladder (below). Exploring divers look for things like living starfish, mussels, sponge and other forms of life. All of these give clues about age and formation of the sea floor. These men can work 100 feet underwater but they have to work fast, for they have only about 95 minutes out of every 24 hours.

Exploring for Petroleum

Another important instrument is the GRAVITY METER. It measures the gravitational pull of the earth, which is not the same at all points. Variations may be slight but still give a clue about the kind and depth of underground rock layers. Here at left an Arabian crewman on an exploration team is using a gravity meter. A third and very important instrument for giving clues to the oil explorers is called a SEISMOGRAPH. The seismograph measures and charts vibrations of the earth. Oil hunters make a little earthquake by drilling a hole in the ground and setting off a small charge of dynamite at the bottom.Waves are set up like the waves made when a stone is thrown into a still pond.

Below is a geophone, sometimes called a "pickup" or a "bug", but usually called a "jug". These jugs, which come in many sizes, some bigger than this one and some as small as a spool of thread, are a form of microphone. They are wired by cable to a seismograph generally installed in a moving truck unit. They transmit to it electrical impulses of the small underground explosions set up by the geophysical crews.

Geophysicists (experts in the sciences of the earth) also help search for oil. They use instruments to tell what goes on underneath the surface of the land. One of the most important instruments used by them is called a MAGNETOMETER. It measures the strength and variations of the earth's magnetic field which can provide clues about rock layers. This Australian aircraft (above), used for making oil exploration surveys, has a magnetometer attached to the tail. Chapter Two

Right, the last connection before exploding a charge is made. The shot holes have been filled with their sticks of dynamite and jugs have all been laid.

Now the seismological crew at their trailer base, right, prepare to set off the charges that will give them a "picture" of the underground.

Exploring for Petroleum

Here, in Louisiana, U.S.A., a very strange-looking car, called a marsh buggy, carries supplies, and tows the crew who will lay the cables and place the jugs. Right, a crew member attaches a piece of bunting to a mesquite tree Texas, U.S.A., to mark an area chosen for testing with explosives. Above, in Texas, U.S.A., a crew member is laying a connecting rubber-covered conductor cable to run underwater between jugs.

Chapter Two

Another team of researchers who give clues to oil explorers are the men who examine and study fossils taken from drill cuttings or core samples. In this laboratory in Peru, S.A., you can see an enlargement of a selection of some of the smallest fossils. Fossils are the skeletons of marine animals that lived in the onetime seas. They are sometimes so small that a large one could be mistaken for a grain of sand. But to those who study fossils, each shape and size tells a story about the age of underground rock layers. This helps the oilman guess how deep he may have to drill before expecting oil. It may indicate oil so deep he cannot afford to chance it. Exploring for Petroleum

|

This is a seismogram, at left, the map the jugs make. These squiggles can be translated by experts to give information about the shape and character of underground formations. This is only part of the information that will determine whether or not to drill in the area under study.

This is a seismogram, at left, the map the jugs make. These squiggles can be translated by experts to give information about the shape and character of underground formations. This is only part of the information that will determine whether or not to drill in the area under study.