Gaulish language

When Cicero's brother Quintus was besieged by the Nervii in Gaul, Julius Caesar sent him a secret message -- in Greek, not Latin, so it could not be read by the enemy if they intercepted it. This is because the Latin and Gaulish languages were very similar to each other, whereas Greek was only a distant relation (and also had a different alphabet). Unfortunately the Gauls have left us no literature, so the two ancient European languages we normally study are Latin and Greek. Despite the similarity, Gaulish was not an Italic language like Latin, but belonged to the Celtic language group, whose modern derivatives include Gaelic, Welsh and Irish. The ancient Celts were variously called Keltoi, Celtae, Galatae or Galli, which are really four different forms of the same name. Around 390 BC the Gauls sacked Rome. In 279 BC they attacked Delphi, and some of them settled in north-western Turkey: these were the Galatians, whose descendants received an epistle from St. Paul. The western Celts lived mostly in northern Italy, France and Britain, and these were the 'Gauls' encountered by Caesar. Our sketchy knowledge of the Gaulish language comes from notices in classical authors and from a small number of Gaulish inscriptions. The longest and most famous of these is the Coligny calendar, preserved on two bronze tablets found in 1897 at Bourg in eastern France. This is a lunar calendar with months of 29 days; the lunar time-reckoning of the Gauls is mentioned by Caesar (Gallic War 6.18). Many Gaulish words closely resemble their Latin counterparts:

Caesar's civitates Aremoricae are those who live are more (= ante mare). His opponent Vercingetorix is the over-king (ver-rix) of warriors (cingetos = Irish cinged 'champion') In the Coligny calendar, the verb divertomu appears at the end of each month and means 'we turn aside (to a different month)': its Latin equivalent is the very similar divertimus. The verb comeimu means 'we go together' (Latin con - 'together' + imus 'we go', from eo, ire). The close similarity of Gaulish and Latin declensions is clear from this example:

Some Gaulish words have no Latin equivalent, because they refer to things unknown at Rome: sapo "soap" (Romans used olive oil instead), cervesia 'beer' (Romans drank wine), tunna 'barrel' (Romans preferred clay storage jars), bracae 'trousers' (Romans wore a toga or tunic). Our word 'beaver' is related to beber, the Gaulish name for this animal, from which comes the Gaulish town-name Bibracte. (The Roman equivalent, castor, is possibly the origin of our 'castor' oil, which has a certain resemblance to a nauseous, bitter-tasting oily medicine formerly extracted from the bodies of beavers.) The similarity of Gaulish to Latin helped it to disappear. Under Roman rule, the Gauls found it relatively easy to learn Latin, and eventually forgot their own language. By the Late Empire, when Gaul was overrun by the Germanic Franks, Gaulish was close to extinct. This explains why modern French is based on Latin and Frankish rather than Gaulish. © L. A. Curchin

The Verbal structure of Gaulish is still somewhat of a shadowy area. While we are normally able to recognize verbs in the inscriptions, in quite a few instances it is hard to properly dissect the verb and determine its meaning. For comparison, some Celtiberian [CIB] and Lepontic forms have also been given here. Examples of Verbal-Forms From Inscriptions ST SG. UEDIUMI [UEDIU - MI "I pray"] ND SG GABAS ["you have taken"] RD SG DEDOR ["It is done"] ST PL DIUERTOMU [DE-UERT-OMU "we turn out of"] ND PL BIIETE ["you all shall be"] RD PL SENANT Gallo-Greek inscription:...DOIIA. The text can be dated between 170-91 B.C.E. Coin "Dubnoreix". Dubnoreix (or "Dumnoreix") was a leader of the Hedui (Bibracte, near Dijon) in the 1st century B.C.E.

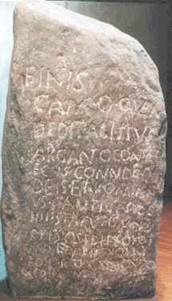

Sacrifice, 2nd / 1st century B.C.E.: bilangual stone ("schiste"), Vercelli, Italy (more)

|

The Gaulish Verbal System

The Gaulish Verbal System