Aptitude and Intelligence

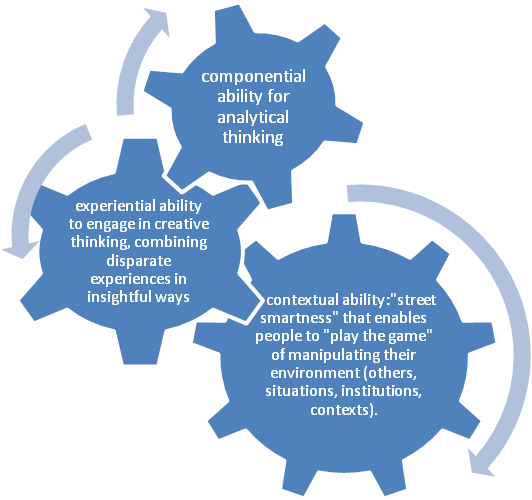

The learning theories, types of learning, and other processes that have so far been explained in this chapter deal with mental perception, storage, and recall. Little has been said about two related and somewhat controversial issues in learning psychology: aptitude and intelligence. In brief, the questions are: - Is there such a thing as foreign language aptitude? If so, what are its properties? Can they be reliably measured? Are aptitudinal factors predictive of success in learning a foreign language? - What is intelligence? How is intelligence defined in terms of the foreign language learning process? What kinds of intelligence are related to foreign language learning? Aptitude Do certain people have a "knack" for learning foreign languages? Anecdotal evidence would suggest that, for a variety of causal factors, some people are indeed able to learn languages faster and more efficiently than others. One perspective of looking at such aptitude is the identification of a number of characteristics of successful language learners. Risk-taking behavior, memory efficiency, intelligent guessing, and ambiguity tolerance are but a few of the many variables that have been cited. A more traditional way of examining what we mean by aptitude is through a historical progression of research that began around the middle of the twentieth century with John Carroll's (Carroll & Sapon 1958) construction of the Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT). The MLAT required prospective language learners (before they began to learn a foreign language) to perform such tasks as learning numbers, listening, detecting spelling clues and grammatical patterns, and memorizing, all either in the native language, English, or utilizing words and morphemes from a constructed, hypothetical language. The MLAT was considered to be independent of a specific foreign language, and therefore predictive of success in the learning of any language. This test, along with another similar one, the Pimsleur Language Aptitude Battery (PLAB) (Pimsleur 1966), was used for some time in such contexts as Peace Corps volunteer training programs to help predict successful language learners. In the decade or so following their publication, these two aptitude tests were quite well received by foreign language teachers and administrators. Since then, their popularity has steadily waned, with few attempts to experiment with alternative measures of language aptitude (Skehan 1998; Parry & Child 1990). Two factors account for this decline. First, even though the MLAT and the PLAB claimed to measure language aptitude, it soon became apparent that they simply reflected the general intelligence or academic ability of a student. At best, they measured ability to perform focused, analytical, context-reduced activities that occupy a student in a traditional language classroom. They hardly even began to tap into the kinds of learning strategies and styles that recent research (Cohen 1998; Reid 1995; Ehrman 1990; Oxford 1990b, 1996, for example) has shown to be crucial in the acquisition of communicative competence in context-embedded situations. As we will see in the next chapter, learners can be successful for a multitude of reasons, many of which are much more related to motivation and determination than to so-called "native" abilities (Lett & O'Mara 1990). Second, how is one to interpret a language aptitude test? Rarely does an institution have the luxury or capability to test people before they take a foreign language in order to counsel certain people out of their decision to do so. And in cases where an aptitude test might be administered, such a test clearly biases both student and teacher. Both are led to believe that they will be successful or unsuccessful, depending on the aptitude test score, and a self-fulfilling prophecy is likely to occur. It is better for teachers to be optimistic for students, and in the early stages of a student's process of language learning, to monitor styles and strategies carefully, leading the student toward strategies that will aid in the process of learning and away from those blocking factors that will hinder the process. Only a few isolated recent efforts have continued to address foreign language aptitude and success (Harley & Hart 1997; Sasaki 1993a, 1993b, for example). Skehan's (1998) bold attempts to pursue the construct of aptitude have exposed some of the weaknesses of aptitude constructs, but unfortunately have not yielded a coherent theory of language aptitude. So today the search for verifiable factors that make up aptitude, or "knack," is headed in the direction of a broader spectrum of learner characteristics. Some of those characteristics fall into the question of intelligence and foreign language learning. How does general cognitive ability intersect with successful language learning? Intelligence Intelligence has traditionally been defined and measured in terms of linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities. Our notion of IQ (intelligence quotient) is based on several generations of testing of these two domains, stemming from the research of Alfred Binet early in the twentieth century. Success in educational institutions and in life in general seems to be a correlate of high IQ. In terms of Ausubel's meaningful learning model, high intelligence would no doubt imply a very efficient process of storing items that are particularly useful in building conceptual hierarchies and systematically pruning those that are not useful. Other cognitive psychologists have dealt in a much more sophisticated way with memory processing and recall systems. In relating intelligence to second language learning, can we say simply that a "smart" person will be capable of learning a second language more successfully because of greater intelligence? After all, the greatest barrier to second language learning seems to boil down to a matter of memory, in the sense that if you could just remember everything you were ever taught, or you ever heard, you would be a very successful language learner. Or would you? It appears that our "language learning IQs" are much more complicated than that. Howard Gardner (1983) advanced a controversial theory of intelligence that blew apart our traditional thoughts about IQ. Gardner described seven different forms of knowing which, in his view, provide a much more comprehensive picture of intelligence. Beyond the usual two forms of intelligence (listed as 1 and 2 below), he added five more: 1) linguistic; 2) logical-mathematical; 3) spatial (the ability to find one's way around an environment, to form mental images of reality, and to transform them readily); 4) musical (the ability to perceive and create pitch and rhythmic patterns); 5) bodily-kinesthetic (fine motor movement, athletic prowess); 6) interpersonal (the ability to understand others, how they feel, what motivates them, how they interact with one another); 7) intrapersonal intelligence (the ability to see oneself, to develop a sense of self-identity). Gardner maintained that by looking only at the first two categories we rule out a great number of the human being's mental abilities; we see only a portion of the total capacity of the human mind. Moreover, he showed that our traditional definitions of intelligence are culture-bound. The "sixth-sense" of a hunter in New Guinea or the navigational abilities of a sailor in Micronesia are not accounted for in our Westernized definitions of IQ. In a likewise revolutionary style, R. Sternberg has also been shaking up the world of traditional intelligence measurement. In his "triarchic" view of intelligence, Sternberg proposed three types of "smartness"(illustration – 2.2).

Illustration 2.2 - Three types of smartness by Robert Stenberg Sternberg contended that too much of psychometric theory is obsessed with mental speed, and therefore dedicated his research to tests that measure insight, real-life problem solving, "common sense," getting a wider picture of things, and other practical tasks that are closely related to success in the real world. Finally, in another effort to remind us of the bias of traditional definitions and tests of intelligence, Daniel Goleman's Emotional Intelligence (1995) is persuasive in placing emotion at the seat of intellectual functioning. The management of even a handful of core emotions—anger, fear, enjoyment, love, disgust, shame, and others—drives and controls efficient mental or cognitive processing. Even more to the point, Goleman argued that "the emotional mind is far quicker than the rational mind, springing into action without even pausing to consider what it is doing. Its quickness precludes the deliberate, analytic reflection that is the hallmark of the thinking mind" (Goleman 1995). Gardner's sixth and seventh types of intelligence (inter- and intrapersonal) are of course laden with emotional processing, but Goleman would place emotion at the highest level of a hierarchy of human abilities. By expanding constructs of intelligence as Gardner, Sternberg, and Goleman have done, we can more easily discern a relationship between intelligence and second language learning. In its traditional definition, intelligence may have little to do with one's success as a second language learner: people within a wide range of IQs have proven to be successful in acquiring a second language. But Gardner attaches other important attributes to the notion of intelligence, attributes that could be crucial to second language success. Musical intelligence could explain the relative ease that some learners have in perceiving and producing the intonation patterns of a language. Bodily-kinesthetic modes have already been discussed in connection with the learning of the phonology of a language. Interpersonal intelligence is of obvious importance in the communicative process. Intrapersonal factors will be discussed in detail in Chapter 6 of this book. One might even be able to speculate on the extent to which spatial intelligence, especially a "sense of direction," may assist the second culture learner in growing comfortable in a new environment. Sternberg's experiential and contextual abilities cast further light on the components of the "knack" that some people have for quick, efficient, unabashed language acquisition. Finally, the EQ (emotional quotient) suggested by Goleman may be far more important than any other factor in accounting for second language success both in classrooms and in untutored contexts. Educational institutions have recently been applying Gardner's seven intelligences to a multitude of school-oriented learning. Thomas Armstrong (1993, 1994), for example, has focused teachers and learners on "seven ways of being smart," and helped educators to see that linguistics and logical-mathematical intelligences are not the only pathways to success in the real world. A high IQ in the traditional sense may garner high scholastic test scores, but may not indicate success in business, marketing, art, communications, counseling, or teaching. Quite some time ago, Oiler suggested, in an eloquent essay, that intelligence may after all be language-based. "Language may not be merely a vital link in the social side of intellectual development, it may be the very foundation of intelligence itself" (1981a). According to Oiler, arguments from genetics and neurology suggest "a deep relationship, perhaps even an identity, between intelligence and language ability". The implications of Oiler's hypothesis for second language learning are enticing. Both first and second languages must be closely tied to meaning in its deepest sense. Effective second language learning thus links surface forms of a language with meaningful experiences, as we have already noted in Ausubel's learning theory. The strength of that link may indeed be a factor of intelligence in a multiple number of ways. We have much to gain from the understanding of learning principles that have been presented here, and of the various ways of understanding what intelligence is. Some aspects of language learning may call upon a conditioning process; other aspects require a meaningful cognitive process; others depend upon the security of supportive co-learners interacting freely and willingly with one another; still others are related to one's total intellectual structure. Each aspect is important, but there is no consistent amalgamation of theory that works for every context of second language learning. Each teacher has to adopt a somewhat intuitive process of discerning the best synthesis of theory for an enlightened analysis of the particular context at hand. That intuition will be nurtured by an integrated understanding of the appropriateness and of the strengths and weaknesses of each theory of learning.

|