Try to find additional information about black and white holes.

2. Find out the names dealt with these problems/ approaches/ theories/ hypotheses. 3. Present your ideas on the given subject for the students' research society.

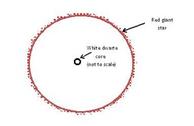

Let us first consider what theory tells us will be the ultimate fate of our sun. The sun has been in existence for some five thousand million years. In another 5-6 thousand million years it will begin to expand in size, swelling inexorably outwards until its surface reaches to about the orbit of the earth. It will then have become a type of star known as a red giant. Many red giants are observed elsewhere in the heavens, two of the best known being Aldebaran in Taurus and Betelgeuse in Orion. All the time that its surface is expanding, there will be, at its very core, an exceptionally dense small concentration of matter, which steadily grows. This dense core will have the nature of a white dwarf star (Fig. 1). White dwarf stars, when on their own, are actual stars whose material is concentrated to extremely high density, such that a ping-pong ball filled with their material would weigh several hundred tonnes! Such stars are observed in the heavens, in quite considerable numbers: perhaps some ten per cent of the luminous stars in our Milky Way galaxy are white dwarfs. The most famous white dwarf is the companion of Sirius, whose alarmingly high density had provided a great observational puzzle to astronomers in the early part of this century. Later, however, this same star provided a marvellous confirmation of physical theory (originally by R. H. Fowler, in around 1926) – according to which, some stars could indeed have such a large density, and would be held apart by 'electron degeneracy pressure', meaning that it is Pauli's quantum-mechanical exclusion principle, as applied to electrons, that is preventing the star from collapsing gravitationally inwards. Any red giant star will have a white dwarf at its core, and this core will be continually gathering material from the main body of the star. Eventually, the red giant will be completely consumed by this parasitic core, and an actual white dwarf – about the the size of the earth – is all that remains. Our sun will be expected to exist as a red giant for 'only' a few thousand million years. Afterwards, in its last 'visible' incarnation – as a slowly cooling dying ember1 of a white dwarf – the sun will persist for a few more thousands of millions of years, finally obtaining total obscurity as an invisible black dwarf. Not all stars would share the sun's fate. For some, their destiny is a considerably more violent one, and their fate is sealed by what is known as the Chandrasekhar limit: the maximum possible value for the mass of a white dwarf star. According to a calculation performed in 1929 by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, white dwarfs cannot exist if their masses are more than about one and one-fifth times the mass of the sun. (He was a young Indian research student-to-be, who was travelling on the boat from India to England when he made his calculation.) The calculation was also repeated independently in about 1930 by the Russian Lev Landau. The modern somewhat refined value for Chandrasekhar's limit is about

Fig. 1. A red giant star with a white dwarf core. Note that the Chandrasekhar limit is not much greater than the sun's mass, whereas many ordinary stars are known whose mass is considerably greater than this value. What would be the ultimate fate of a star of mass What then happens to the still-collapsing core? Theory tells us that it reaches enormously greater densities even than those alarming ones already achieved inside a white dwarf. The core can stabilize as a neutron star What happens to this collapsing core if the mass of the original star is great enough that even this limit will be exceeded? Many stars are known, of masses ranging between What is a black hole? It is a region of space – or of space-time – within which the gravitational field has become so strong that even light cannot escape from it. Recall that it is an implication of the principles of relativity that the velocity of light is the limiting velocity: no material object or signal can exceed the local light speed. Hence, if light cannot escape from a black hole, nothing can escape. Perhaps the reader is familiar with the concept of escape velocity. This is the speed which an object must attain in order to escape from some massive body. Suppose that body were the earth; then the escape velocity from it would be approximately 40000 kilometres per hour, which is about 25000 miles per hour. A stone which is hurled from the earth's surface (in any direction away from the ground), with a speed exceeding this value, will escape from the earth completely (assuming that we may ignore the effects of air resistance). If thrown with less than this speed, then it will fall back to the earth. (Thus, it is not true that 'everything that goes up must come down'; an object returns only if it is thrown with less than the escape velocity!) For Jupiter, the escape velocity is 220000 kilometres per hour i.e. about 140000 miles per hour; and for the sun it is 2200000 kilometres per hour, or about 1400000 miles per hour. Now suppose we imagine that the sun's mass were concentrated in a sphere of just one quarter of its present radius, then we should obtain an escape velocity which is twice as great as its present value; if the sun were even more concentrated, say in a sphere of one-hundredth of its present radius, then the velocity would be ten times as great. We can imagine that for a sufficiently massive and concentrated body, the escape velocity could exceed even the velocity of light! When this happens, we have a black hole. In Fig. 2, I have drawn a space-time diagram depicting the collapse of a body to form a black hole (where I am assuming that the collapse proceeds in a way that maintains spherical symmetry reasonably closely, and where I have suppressed one of the spatial dimensions). The light cones have been depicted, and, as we recall from the discussion of general relativity, these indicate the absolute limitations on the motion of a material object or signal. Note that the cones begin to tip inwards towards the centre, and the tipping gets more and more extreme the more central they are. There is a critical distance from the centre, referred to as the Schwarzschild radius, at which the outer limits of the cones become vertical in the diagram. At this distance, light (which must follow the light cones) can simply hover above the collapsed body, aid all the outward velocity that the light can muster is just barely enough to counteract the enormous gravitational pull. The (3-)surface in space-time traced out, at the Schwarzschild radius, by this hovering light (i.e. the light's entire history) is referred to as the (absolute) event horizon of the black hole. Anything that finds itself within the event horizon is unable to escape or even to communicate with the outside world. This can be seen from the tipping of the cones, and from the fundamental fact that all motions and signals are constrained to propagate within (or on) these cones. For a black hole formed by the collapse of a star of a few solar masses, the radius of the horizon would be a few kilometres. Much larger black holes are expected to reside at galactic centres. Our own Milky Way galaxy may well contain a black hole of about a million solar masses, and the radius of the hole would then be a few million kilometres.

The actual material body which collapses to form the black hole will end up totally within the horizon, and so it is then unable to communicate with the outside. We shall be considering the probable fate of the body shortly. For the moment, it is just the space-time geometry created by its collapse that concerns us – a space-time geometry with profoundly curious implications. Let us imagine a brave (or foolhardy?) astronaut B, who resolves to travel into a large black hole, while his more timid (or cautious?) companion A remains safely outside the event horizon. Let us suppose that A endeavours to keep В in view for as long as possible. What does A see? It may be ascertained from Fig. 2 that the portion of B 's history (i.e. B 's world-line) which lies inside the horizon will never be seen by A, whereas the portion outside the horizon will all eventually have become visible to A – though B 's moments immediately preceding his plunge across the horizon will be seen by A only after longer and longer periods of waiting. Suppose that В crosses the horizon when his own watch registers 12 o'clock. That occurrence will never actually be witnessed by A, but the watch-readings What about poor B? What will be his experience? It should first be pointed out that there will be nothing whatever noticeable by В at the moment of his crossing the horizon. He glances at his watch as it registers around 12 o'clock and he sees the minutes pass regularly by: Or perhaps it is not so private. All the matter of the collapsed body that formed the black hole in the first place will, in a sense, be sharing the 'same' crunch with him. In fact, if the universe outside the hole is spatially closed, so that the outside matter is also ultimately engulfed in an all-embracing big crunch, then that crunch, also, would be expected to be the 'same' as B 's 'private' one. Despite B 's unpleasant fate, we do not expect that the local physics that he experiences up to that point should be at odds with the physics that we have come to know and understand. In particular, we do not expect that he will experience local violations of the second law of thermodynamics, let alone a complete reversal of the increasing behaviour of entropy. The second law will hold sway just as much inside a black hole as it does elsewhere. The entropy in B 's vicinity is still increasing, right up until the time of his final crunch. To understand how the entropy in a 'big crunch' (either 'private' or 'all-embracing') can indeed be enormously high, whereas the entropy in the big bang had to have been much lower, we shall need to delve a little more deeply into the space-time geometry of a black hole. But before we do so, the reader should catch a glimpse also of Fig. 3 which depicts the hypothetical time-reverse of a black hole, namely a white hole. White holes probably do not exist in nature, but their theoretical possibility will have considerable significance for us. Text 6. Hawking's box: a link with the Weyl curvature hypothesis?

1. Find the film "Time Travel";. 2. Discuss it at the students' on line conference.

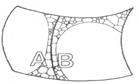

That is as may be, the reader is no doubt thinking, but what has ali this to do with WCH or CQG? True, the second law, as it operates today, may well be part of the operation of R, but where is there any noticeable role for space-time singularities or quantum gravity in these continuing 'everyday' Imagine a sealed box of monstrous proportions. Its walls are taken to be totally reflecting and impervious to any influence. No material object may pass through, nor may any electromagnetic signal, or neutrino, or anything. All must be reflected back, whether they impinge from without or from within. Even the effects of gravity are fobidden to pass through. There is no actual substance out of which such walls could be built. No-one could actually perform the 'experiment' that I shall describe. (Nor would anyone want to, as we shall see!) That is not the point. In a thought experiment one strives to uncover general principles from the mere mental consideration of experiments that one might perform. Technological difficulties are ignored, provided they have no bearing on the general principles under consideration. In our case, the difficulties in constructing the walls for our box are to be regarded as purely 'technological' for this purpose, so these difficulties will be ignored. Inside the box is a large amount of material substance, of some kind. It does not matter much what this substance is. We are concerned only with its total mass M, which should be very large, and with the large volume V of the box which contains it. What are we to do with our expensively constructed box and its totally uninteresting contents? The experiment is to be the most boring imaginable. We are to leave it untouched – forever! The question that concerns us is the ultimate fate of the contents of the box. According to the second law of thermodynamics, its entropy should be increasing. The entropy should increase until the maximum value is attained, the material having now reached 'thermal equilibrium'. Nothing much would happen from then on, were it not for 'fluctuations' where (relatively) brief departures from thermal equilibrium are temporarily attained. In our situation, we assume that M is large enough, and V is something appropriate (very large, but not too large), so that when 'thermal equilibrium' is attained most of the material has collapsed into a black hole, with just a little matter and radiation running round it – constituting a (very cold!) so-called 'thermal bath', in which the black hole is immersed. To be definite, we could choose M to be the mass of the solar system and V to be the size of the Milky Way galaxy! Then the temperature of the 'bath' would be only about To understand more clearly the nature of this equilibrium and these fluctuations, let us recall the concept of phase space, particularly in connection with the definition of entropy. Figure 1 gives a schematic description of the whole phase space Pof the contents of Hawking's box. As we recall, a phase space is a large-dimensional space, each single point of which represents an entire possible state of the system under consideration – here the contents of the box. Thus, each point of P codifies the positions and momenta of all the particles that are present in the box, in addition to all the necessary information about the space-time geometry within the box. The subregion B(of P) on the right of Fig. 1 represents the totality of all states in which there is a black hole within the box (including all cases in which there is more than one black hole), whilst the subregion A on the left represents the totality of all states free of black holes. We must suppose that each of the regions Aand B is further subdivided into smaller compartments according to the 'coarse graining' that is necessary for the precise definition of entropy, but the details of this will not concern us here. All we need to note at this stage is that the largest of these compartments – representing thermal equilibrium, with a black hole present – is the major portion of B, whereas the (somewhat smaller) major portion of Ais the compartment representing what appears to be thermal equilibrium, except that no black hole is present.

Fig. 1. The phase space P of Hawking's box. The region A corresponds to the situations where there is no black hole in the box and B, to where there is a black hole (or more than one) in the box. Recall that there is a field of arrows (vector field) on any phase space, representing the temporal evolution the physical system. Thus, to see what will happen next in our system, we simply follow along arrows in P. Some of these arrows will cross over from the region Ainto the region B. This occurs when a black hole first forms by the gravitational collapse of matter. Are there arrows crossing back again from region B into region A? Yes there are, but only if we take into account the phenomenon of Hawking evaporation. According to the strict classical theory of general relativity, black holes can only swallow things; they cannot emit things. But by taking quantum-mechanical effects into account, Hawking (1975) was able to show that black holes ought, at the quantum level, to be able to emit things after all, according to the process of Hawking radiation. (This occurs via the quantum process of 'virtual pair creation', whereby particles and anti-particles are continually being created out of the vacuum – momentarily – normally only to annihilate one another immediately afterwards, leaving no trace. When a black hole is present, however, it can 'swallow' one of the particles of such a pair before this annihilation has time to occur, and its partner may escape the hole. These escaping particles constitute Hawking's radiation.) In the normal way of things, this Hawking radiation is very tiny indeed. But in the thermal equilibrium state, the amount of energy that the black hole loses in Hawking radiation exactly balances the energy that it gains in swallowing other 'thermal particles' that happen to be running around in the 'thermal bath' in which the black hole finds itself. Occasionally, by a 'fluctuation', the hole might emit a little too much or swallow too little and thereby lose energy. In losing energy, it loses mass (by Einstein's

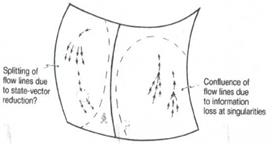

Fig. 2. The 'Hamiltonian flow' of the contents of Hawking's box. Flow lines crossing from A to B represent collapse to a black hole; and those from B to A, disappearance of a black hole by Hawking evaporation. At this point, I should make a remark about what is meant by a 'fluctuation'. The phase-space points that belong to a single compartment are to be regarded as (macroscopically) 'indistinguishable' from one another. Entropy increases because by following the arrows we tend to get into huger and huger compartments as time progresses. Ultimately, the phase-space point loses itself in the hugest compartment of all, namely that corresponding to thermal equilibrium (maximum entropy). However, this will be true only up to a point. If one waits for long enough, the phase-space point will eventually find a smaller compartment, and the entropy will accordingly go down. This would normally not be for long (comparatively speaking) and the entropy would soon go back up again as the phase-space point re-enters the largest compartment. This is a fluctuation, with its momentary lowering of entropy. Usually, the entropy does not fall very much, but very, very occasionally a huge fluctuation will occur, and the entropy could be lowered substantially – and perhaps remain lowered for some considerable length of time. This is the kind of thing that we need in order to get from region Bto region A via the Hawking evaporation process. A very large fluctuation is needed because a tiny compartment has to be passed through just where the arrows cross over between Band A. Likewise, when our phase-space point lies inside the major compartment within A (representing a thermal equilibrium state without black holes), it will actually be a very long while before a gravitational collapse takes place and the point moves into B. Again a large fluctuation is needed. (Thermal radiation does not readily undergo gravitational collapse!) Are there more arrows leading from A to B, or from Bto A, or is the number of arrows the same in each case? This will be an important issue for us. To put the question another way, is it 'easier' for Nature to produce a black hole by gravitationally collapsing thermal particles, or to get rid of a black hole by Hawking radiation, or is each as 'difficult' as the other? Strictly speaking it is not the 'number' of arrows that concerns us, but the rate of flow of phase-space volume. Think of the phase space as being filled with some kind of (high-dimensional!) incompressible fluid. The arrows represent the flow of this fluid. Recall Liouville's theorem. Liouville's theorem asserts that the phase-space volume is preserved by the flow, which is to say that our phase-space fluid is indeed incompressible! Liouville's theorem seems to be telling us that the flow from Ato Bmust be equal to the flow from B to Abecause the phase-space 'fluid', being incompressible, cannot accumulate either on one side or the other. Thus it would appear that it must be exactly equally 'difficult' to build a black hole from thermal radiation as it is to destroy one! This, indeed, was Hawking's own conclusion, though he came to this view on the basis of somewhat different considerations. Hawking's main argument was that all the basic physics that is involved in the problem is time-symmetrical (general relativity, thermodynamics, the standard unitary procedures of quantum theory), so if we run the clock backwards, we should get the same answer as if we run it forwards. This amounts simply to reversing the directions of all the arrows in P. It would then indeed follow also from this argument that there must be exactly as many arrows from Ato Bas from B to In any case, the suggestion is not really compatible with the ideas that I am putting forward here. I have argued that whereas black holes ought to exist, white holes are forbidden because of the Weyl curvature hypothesis! WCH introduces a time-asymmetry into the discussion which was not considered by Hawking. It should be pointed out that since black holes and their space-time singularities are indeed very much part of the discussion of what happens inside Hawking's box, the unknown physics that must govern the behaviour of such singularities is certainly involved. Hawking takes the view that this unknown physics should be a time-symmetric quantum gravity theory, whereas I am claiming that it is the time-flasymmetric CQG! I am claiming that one of the major implications of COG should be WCH (and, consequently, the second law of thermodynamics in the form that we know it), so we should try to ascertain the implications of WCH for our present problem. Let us see how the inclusion of WCH affects the discussion of the flow of our 'incompressible fluid' in P. In space-time, the effect of a black-hole singularity is to absorb and destroy all the matter that impinges upon it. More importantly for our present purposes, it destroys information. The effect of this, in P, is that some flow lines will now merge together (see Fig. 3). Two states which were previously different can become the same as soon as the information that distinguishes between them is destroyed. When flow lines in Pmerge together we have an effective violation of Liouville's theorem. Our 'fluid' is no longer incompressible, but it is being continually annihilated within region B!

Fig. 3. In region B flow lines must come together because of information loss at black-hole singularities. Is this balanced by a creation of flow lines due to the quantum procedure R (primarily in region A)? Now we seem to be in trouble. If our 'fluid' is being continually destroyed in region B, then there must be more flow lines from Ato B than there are from B to A – so it is 'easier' to create a black hole than to destroy one after all! This could indeed make sense were it not for the fact that now more 'fluid' flows out of region A than re-enters it. There are no black holes in region A – and white holes have been excluded by WCH – so surely Liouville's theorem ought to hold perfectly well in region A! However, we now seem to need some means of 'creating fluid' in region A to make up the loss in region B. What mechanism can there be for increasing the number of flow lines? What we appear to require is that sometimes one and the same state can have more than one possible outcome (i.e. bifurcating flow lines). This kind of uncertainty in the future evolution of a physical system has the 'smell' of quantum theory about it – the R part. Can it be that R is, in some sense, 'the other side of the coin' to WCH? Whereas WCH serves to cause flow lines to merge within B, the quantum-mechanical procedure R causes flow lines to bifurcate. I am indeed claiming that it is an objective quantum-mechanical process of state-vector reduction (R) which causes flow lines to bifurcate, and so compensate exactly for the merging of flow lines due to WCH (Fig. 3)! In order for such bifurcation to occur, we need R to be time-asymmetric, as we have already seen: recall our experiment above, with the lamp, photo-cell, and half-silvered mirror. When a photon is emitted by the lamp, there are two (equally probable) alternatives for the final outcome: either the photon reaches the photo-cell and the photo-cell registers, or the photon reaches the wall at A and the photo-cell does not register. In the phase space for this experiment, we have a flow line representing the emission of the photon and this bifurcates into two: one describing the situation in which the photo-cell fires and the other, the situation in which it does not. This appears to be a genuine bifurcation, because there is only one allowed input and there are two possible outputs. The other input that one might have had to consider was the possibility that the photon could be ejected from the laboratory wall at B, in which case there would be two inputs and two outputs. But this alternative input has been excluded on the grounds of inconsistency with the second law of thermodynamics – i.e. from the point of view expressed here, finally with WCH, when the evolution is traced into the past. I should re-iterate that the viewpoint that I am expressing is not really a 'conventional' one – though it is not altogether clear to me what a 'conventional' physicist would say in order to resolve all the issues raised. (I suspect that not many of them have given these problems much thought!) I have Finally, there is a serious point that I have glossed over. I started the discussion by assuming that we had a classical phase space – and Liouville's theorem applies to classical physics. But then the quantum phenomenon of Hawking radiation needed to be considered. (And quantum theory is actually also needed for the finite-dimensionality as well as finite volume of P). As we saw, the quantum version of phase space is Hilbert space, so we should presumably have used Hilbert space rather than phase space for our discussion throughout. In Hilbert space there is an analogue of Liouville's theorem. It arises from what is called the 'unitary' nature of the time-evolution U. Perhaps my entire argument could be phrased entirely in terms of Hilbert space, instead of classical phase space, but it is difficult to see how to discuss the classical phenomena involved in the space-time geometry of black holes in this way. My own opinion is that for the correct theory neither Hilbert space nor classical phase space would be appropriate, but one would have to use some hitherto undiscovered type of mathematical space which is intermediate between the two. Accordingly, my argument should be taken only at the heuristic level, and it is merely suggestive rather than conclusive. Nevertheless, I do believe that it provides a strong case for thinking that WCH and R are profoundly linked and that, consequently, R must indeed be a quantum gravity effect. To re-iterate my conclusions: I am putting forward the suggestion that quantum-mechanical state-vector reduction is indeed the other side of the coin to WCH. According to this view, the two major implications of our sought-for 'correct quantum gravity' theory (CQG) will be WCH and R. The effect of WCH is confluence of flow lines in phase space, while the effect of R is an exactly compensating spreading of flow lines. Both processes are intimately associated with the second law of thermodynamics. Note that the confluence of flow lines takes place entirely within the region B, whereas flow-line spreading can take place either within A or within B. Recall that Arepresents the absence of black holes, so that state-vector reduction can indeed take place when black holes are absent. Clearly it is not necessary to have a black hole in the laboratory in order that R be effected (as with our experiment with the photon, just considered). We are concerned here only with a general overall balance between possible things which might happen in a situation. On the view that I am expressing, it is merely the possibility that black holes might form at some stage (and consequently then destroy information) which must be balanced by the lack of determinism in quantum theory!

|

where

where  is the mass of the sun, i.e.

is the mass of the sun, i.e.

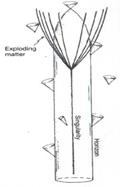

, for example? Again, according to established theory, the star should swell to become a red giant, and its white-dwarf core would slowly acquire mass, just as before. However, at some critical stage the core will reach Chandrasekhar's limit, and Pauli's exclusion principle will be insufficient to hold it apart against the enormous gravitationally induced pressures. At this point, or thereabouts, the core will collapse catastrophically inwards, and hugely increased temperatures and pressures will be encountered. Violent nuclear reactions take place, and an enormous amount of energy is released from the core in the form of neutrinos. These heat up the outer regions of the star, which have been collapsing inwards, and a stupendous explosion ensues. The star has become a supernova!

, for example? Again, according to established theory, the star should swell to become a red giant, and its white-dwarf core would slowly acquire mass, just as before. However, at some critical stage the core will reach Chandrasekhar's limit, and Pauli's exclusion principle will be insufficient to hold it apart against the enormous gravitationally induced pressures. At this point, or thereabouts, the core will collapse catastrophically inwards, and hugely increased temperatures and pressures will be encountered. Violent nuclear reactions take place, and an enormous amount of energy is released from the core in the form of neutrinos. These heat up the outer regions of the star, which have been collapsing inwards, and a stupendous explosion ensues. The star has become a supernova! , where now it is neutron degeneracy pressure – i.e. the Pauli principle applied to neutrons – that is holding it apart. The density would be such that our ping-pong ball containing neutron star material would weigh as much a the asteroid Hermes (or perhaps Mars's moon Deimos). This is the kind оf density found inside the very nucleus itself! (A neutron star is like a huge atomic nucleus, perhaps some ten kilometres in radius, which is, however, extremely tiny by stellar standards!) But there is now a new limit, analogous to Chandrasekhar's (referred to as the Landau-Oppenheimer-Volkov limit) whose modern (revised) value is very roughly

, where now it is neutron degeneracy pressure – i.e. the Pauli principle applied to neutrons – that is holding it apart. The density would be such that our ping-pong ball containing neutron star material would weigh as much a the asteroid Hermes (or perhaps Mars's moon Deimos). This is the kind оf density found inside the very nucleus itself! (A neutron star is like a huge atomic nucleus, perhaps some ten kilometres in radius, which is, however, extremely tiny by stellar standards!) But there is now a new limit, analogous to Chandrasekhar's (referred to as the Landau-Oppenheimer-Volkov limit) whose modern (revised) value is very roughly  , above which a neutron star cannot hold itself apart.

, above which a neutron star cannot hold itself apart. and

and  , for example. It would seem highly unlikely that they would invariably throw off so much mass that the resulting core necessarily lies below this neutron star limit. The expectation is that, instead, a black hole will result.

, for example. It would seem highly unlikely that they would invariably throw off so much mass that the resulting core necessarily lies below this neutron star limit. The expectation is that, instead, a black hole will result.

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , etc. will be successively seen by A (at roughly equal intervals, from A 's point of view). In principle, В will always remain visible to A and would appear to be forever hovering just above the horizon, his watch edging ever more slowly towards the fateful hour of 12:00, but never quite reaching it. But, in fact the image of В that is perceived by A would very rapidly become too dim to be discernible. This is because the light from the tiny portion of B 's world-line just outside the horizon has to make do for the whole of the remainder of A 's experienced time. In effect, В will have vanished from A 's view – and the same would be true of the entire original collapsing body. All that A can see will indeed be just a 'black hole'!

, etc. will be successively seen by A (at roughly equal intervals, from A 's point of view). In principle, В will always remain visible to A and would appear to be forever hovering just above the horizon, his watch edging ever more slowly towards the fateful hour of 12:00, but never quite reaching it. But, in fact the image of В that is perceived by A would very rapidly become too dim to be discernible. This is because the light from the tiny portion of B 's world-line just outside the horizon has to make do for the whole of the remainder of A 's experienced time. In effect, В will have vanished from A 's view – and the same would be true of the entire original collapsing body. All that A can see will indeed be just a 'black hole'! ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,….Nothing seems particularly odd about the time

,….Nothing seems particularly odd about the time

of a degree above absolute zero!

of a degree above absolute zero!

) and, according to the rules governing Hawking radiation, it gets a tiny bit hotter. Very very occasionally, when the fluctuation is large enough, it is even possible for the black hole to get into a runaway situation whereby it grows hotter and hotter, losing more and more energy as it goes, getting smaller and smaller until finally it (presumably) disappears completely in a violent explosion! When this happens (and assuming there are no other holes in the box), we have the situation where, in our phase space P, we pass from region Bto region A, so indeed there are arrows from Bto A!

) and, according to the rules governing Hawking radiation, it gets a tiny bit hotter. Very very occasionally, when the fluctuation is large enough, it is even possible for the black hole to get into a runaway situation whereby it grows hotter and hotter, losing more and more energy as it goes, getting smaller and smaller until finally it (presumably) disappears completely in a violent explosion! When this happens (and assuming there are no other holes in the box), we have the situation where, in our phase space P, we pass from region Bto region A, so indeed there are arrows from Bto A!