CHAPTER 7

The formalization of sentence-meaning 7.0 INTRODUCTION This chapter follows on from the preceding one and looks at two historically important and highly influential theories of sentence-meaning which, since the mid-1960s, have been associated with the attempt to formalize the semantic structure of languages within the framework of Chomskyan and non-Chomskyan generative grammar. The first is the Katz-Fodor theory of meaning, which originated in association with what we may now think of as the classical version of Chomsky's theory of transformational-generative grammar. The second theory is a particular version of possible-worlds semantics, initiated also in the late 1960s by Richard Montague, and, having been further developed by his followers, is now widely recognized as one of the most promising approaches to the truly formidable task of accounting for the propositional content of sentences in a mathematically precise and elegant manner. The treatment of both theories is very selective and almost completely non-technical. I have been more concerned to explain some of the basic concepts than to introduce any of the formalism. At the same time, it must be emphasized that modern formal semantics is a technical subject, which cannot be understood without also understanding the mathematical concepts and notation that are a part of it. This chapter should definitely be read in conjunction with the more specialized introductions to formal semantics mentioned in the 'Suggestions for further reading'. Students who have mastered the concepts that are

200 The formalization of sentence-meaning explained below should be able to tackle these other works and, equally important, to contextualize them within the framework of a broader approach to linguistic semantics than is customarily adopted by formal semanticists. There is a sense in which the Katz-Fodor theory is now outdated, as also in much of its detail is the so-called standard theory of transformational grammar. But, as I explain below, taken together, both theories are historically important, in that they introduced linguists to the principle of compositionality, as this is understood in formal semantics. Each of them is widely referred to in textbooks and is still taught in linguistics courses (if only as a foundation upon which to build). In my view, a good knowledge of each is indispensable for anyone who wishes to understand the more recent developments in linguistic semantics. They can also be used, as I use them here, with the more specific purpose of introducing students of linguistics to formal semantics. In the last twenty years or so considerable progress has been made in the formalization of the semantic structure of natural languages. However, as we shall see in the later sections of this chapter, it is so far only a relatively small part of linguistic mean- ing that has been brought within the scope of formal semantics. We begin the chapter by considering the relation between formal semantics and linguistic semantics, as the latter has been defined in Chapter 1; and we end with a (non-technical) discussion of some of the underlying philosophical concepts upon which formal semantics is based. These are generally taken for granted, rather than explained, in more technical works. 7.1 FORMAL SEMANTICS AND LINGUISTIC SEMANTICS The term 'formal semantics' can be given several different interpretations. Originally, it meant "the semantic analysis of formal systems (or formal languages)" - a formal system, or formal language, being one that has been deliberately constructed by logicians, computer scientists, etc. for philosophical or practical purposes. More recently, the term has been applied to the analy- 7.1 Formal semantics and linguistic semantics 201 sis of meaning in natural languages, but usually with a number of restrictions, tacit or explicit, which derive from its philosophical and logical origins. In this book, we are not concerned with formal semantics for its own sake, but only in so far as it is actually or potentially applicable to the analysis of natural languages. I will now introduce the term 'formal linguistic semantics' to refer to that part, or branch, of linguistic semantics which draws upon the methods and concepts of formal semantics for the analysis of the semantic structure of natural languages. In doing so, I am deliberately avoiding commitment, one way or the other, on the question whether natural languages are fundamentally different, seman-tically, from non-natural (i.e., artificial or constructed) languages. Some twenty years ago, Richard Montague, whose own theory of formal semantics we shall be looking at in a later section, gave it as his opinion that there is "no important theoretical difference between natural languages and the artificial languages of logicians" and that it is "possible to comprehend the syntax and semantics of both kinds of languages within a single natural and mathematically precise theory". Whether Montague was right or wrong about this is still unclear. Indeed, given his failure to say exactly what he meant by 'important theoretical difference', it is not obvious that he was making, or intended to make, any kind of empirically confirmable claim about the semantic (and syntactic) structure of natural languages. He was declaring an attitude and, as it turned out, initiating a highly productive, but deliberately restricted, programme of research. Formal linguistic semantics is generally associated with a restricted view of sentence-meaning: the view that sentence-meaning is exhausted by prepositional content and is truth-conditionally explicable. As we have seen in Chapter 6, there are - or would appear to be - various kinds of meaning encoded in the lexical or grammatical structure of sentences which are not readily accounted for in terms of their prepositional content. Two reactions are open to theorists and practitioners of formal linguistic semantics in the face of this difficulty, if they accept, as most of them do, that it is a genuine 202 The formalization of sentence-meaning difficulty. One reaction is to say that what we have identified as a part of sentence-meaning is not in fact encoded in sentences as such, but is the product of the interaction between the meaning, properly so called, of the sentence itself and something else: contextual assumptions and expectations, non-linguistic (encyclopaedic) knowledge, conversational implicatures, etc., and should be handled as a matter of pragmatics rather than semantics. The second reaction is to accept that it is indeed a part of sentence-meaning and to attempt to provide a truth-conditional account of the phenomena by extending the formalism and relaxing some of the restrictions associated with what one may now think of as classical versions of formal semantics. Both attitudes are represented among formal semanticists who have been concerned with the analysis of linguistic meaning in recent years. I have made it clear, in the preceding chapter, that, in my view, formal linguistic semantics has failed, so far, to account satisfactorily for such phenomena as tense, mood and sentence-type and has not been sufficiently respectful of the principle of saving the appearances. I cannot emphasize too strongly, therefore, that, in my view, this failure does not invalidate completely the attempts that have been made to deal with these and other phenomena. The failure of a precise, but inadequate, account often points the way to the construction of an equally precise, but more comprehensive, theory of the same phenomena. And even when it does not do this, it may throw some light, obliquely and by reflection, upon the data that it does not fully illuminate. Many examples of this can be cited. To take but one: so far, no fully satisfactory account of the meaning of the English words, 'some' and 'any' (and their congeners: 'someone', 'anyone', 'something', 'anything', etc.) has been provided within the framework of formal linguistic semantics. Nevertheless, our understanding of the range of potentially relevant factors which determine the selection of one or the other has been greatly increased by the numerous attempts that have been made to handle the data truth-conditionally. Those who doubt that this is so are invited to compare the treatment of 'any' and 'some' in older and more recent pedagogical grammars of English, not to 7.1 Formal semantics and linguistic semantics 203 mention scholarly articles on the topic. They will see immediately that the more recent accounts are eminently more satisfactory. What follows is a deliberately simplified treatment of some of the principal concepts of formal semantics that have been widely invoked by linguists in the analysis of the prepositional content of the sentences of natural languages. No account is taken, in this chapter, of anything other than what is uncontroversially a part of the propositional content of sentences in English. It will be clear, however, from what was said in Chapter 6, that natural languages vary considerably as to what they encode in the grammatical and lexical structure of sentences and that, according to the view adopted in this book, much of sentence-meaning, in many natural languages including English, is non-propositional. Whether formal linguistic semantics can ever cover, or be coextensive with, the whole of linguistic semantics is an open question. Formal linguistic semantics, in its present state of development, is certainly a long way from being co-extensive with linguistic semantics, either theoretically or empirically. But progress is being made, and it is conceivable that, in due course, far more of the insights and findings of non-formal linguistic semantics, traditional and modern, will be successfully formalized (probably by relaxing the restriction of sentence-meaning to what is truth-conditionally explicable). In this connexion, it is worth noting that, as there is a distinction to be drawn between linguistic theory (in the traditional sense of 'theory' in which theories are not necessarily formalized) and theoretical linguistics (as the term 'theoretical linguistics' is nowadays used: i.e., to refer to such parts of linguistic theory as have been formalized, or mathematicized), so there is a distinction to be drawn between semantic theory and theoretical, or formal, semantics. In recent years, each has drawn upon and, in turn, influenced the other; and this process of mutual influence will no doubt con tinue. 204 The formalization of sentence-meaning 7.2 CO M P O S I TI O N A L I T Y, G R A M M AT I C A L A N D S E M A N T I C I S O M O R P H I S M, AND S A V I N G THE APPEARANCES The principle of compositionality has been mentioned already in connexion with the sense of words and phrases. Commonly described as Frege's principle,it is more frequently discussed with reference to sentence-meaning. This is why I have left a fuller treatment of it for this chapter. It is central to formal semantics in all its developments. As it is usually formulated, it runs as follows (with 'composite' substituted for 'complex' or 'compound'): the meaning of a composite expression is a function of the meanings of its component expressions. Three of the terms used here deserve attention; 'meaning', 'expression' and 'function'. I will comment upon each of them in turn and then explain, first, why the principle of compositionality is so important and, second, to what degree it is, or appears to be, valid. (i) 'Meaning', as we have seen, can be given various interpretations. If we restrict it to descriptive meaning, or propositional content, we can still draw a distinction between sense and denotation (see 3.1). Frege's own distinction between sense and reference (drawn originally in German with the terms 'Sinn' and 'Bedeutung') is roughly comparable, and is accepted in broad outline, if not in detail, by most formal semanticists. (Frege, like many formal semanticists, did not distinguish between the denotation of an expression and its reference on particular occasions of utterance: see section 3.1. I will pick up this point in relation to the principle of compositionality presently.) I will take the principle of compositionality to apply primarily to sense. But it may be assumed to apply also to denotation; and, as we shall see in a later section, many formal semanticists have defined sense in terms of a prior notion of denotation. (ii) The term 'expression' is usually left undefined when it is used by linguists. But it is normally taken to include sentences and any of their syntactically identifiable constituents. I have given reasons earlier for distinguishing expressions from forms,' as far as words and phrases are concerned. More controversially perhaps, in also including sentences among the expressions of a 7.2 Compositionality, grammatical and semantic isomorphism 205 language, I have allowed that a sentence, like words and phrases, may have, not only several meanings, but also several forms. I will now assume that there is an identifiable subpart of every sentence that is the bearer of its propositional content, and that this also is an expression to which the principle of compositionality applies. For example, if we take the view that corresponding interrogative and declarative sentences have the same propositional content, we shall say that what they share is an expression (which of itself is neither declarative nor interrogative). Some logicians who have taken this view (as did Frege) have called the expression in which the propositional content is encoded the sentence-radical;but this term has not won more general acceptance, and there is no widely used alternative. I will employ instead the term sentence-kernel,or kernel,which has occasionally been used in linguistics, for grammatical, rather than semantic, analysis. (Indeed, the use that I am making of this term is very close to the use that Chomsky made of the term 'kernel-string' in the earliest version of transformational-generative grammar formalized by him.) The kernel of a sentence (or clause), then, is an expression, which has a form (not necessarily pronounceable) and whose meaning is (or includes) its propositional content. (iii) The term 'function' is being employed in its mathematical sense; i.e., to refer to a rule, formula or operation which assigns a single value to each member of the set of entities in its domain. (It thus establishes either a many-one-to-one or one-to-one correspondence between the members of the domain, D, and the set of values, V: it maps D either into or on to V.) For example, in standard algebras there is an arithmetical function, normally written y = x2, which for any numerical value of x yields a single and determinate numerical value for x2 and thus determines the value of y. Similarly, in the propositional calculus there is a function which for each value of the propositional variables in every well-formed expression maps that expression into the two-member domain {True, False}, or, alternatively and equivalently, {l, 0}. As we saw earlier, this is what is meant by saying that composite propositions are truth-functional. I have now spelled this out in more detail and deliberately introduced,

206 The formalization of sentence-meaning with some redundancy, several of the technical terms that are commonly employed in formal semantics. We shall not go, unnecessarily, into the technical details of formal semantics, but the limited amount of terminology introduced here will be useful later, and it will give readers with a knowledge of elementary set-theory some indication of the mathematical framework within which standard versions of formal semantics operate. But what is the relevance of the notion of compositionality, formalized mathematically, to the semantic analysis of natural-language expressions? First of all, it should be noted that competence in a particular language includes (or supports) the ability to interpret, not only lexically simple expressions, but indefinitely many lexically composite expressions, of the language. Since it is impossible for anyone to have learned the sense of every composite expression in the way that one, presumably, learns the sense of lexemes, formal semanticists argue that there must be some function which determines the sense of composite expressions on the basis of the sense of lexemes. Second, it is reasonable to assume that the sense of a composite expression is a function, not only of the sense of its component lexemes, but also of its grammatical structure. We have made this assumption throughout; and it can be tested empirically in a sufficient number of instances for us to accept it as valid. What is needed, then, in the ideal, is a precisely formulated procedure for the syntactic composition of all the well-formed lexically composite expressions in a language, coupled with a procedure for determining the semantic effect, if any, of each process or stage of syntactic composition. This is what formal semantics seeks to provide. Formal linguistic semantics, as such, is not committed to any particular theory of syntax. Nor does it say anything in advance about the closeness of the correspondence between grammatical and semantic structure in natural languages. There is a wide range of options on each of these issues. That there is some degree of correspondence, or isomorphism, between grammatical and semantic structure is intuitively obvious and can be demonstrated, in particular instances, by appealing to various kinds of 7.2 Compositionality, grammatical and semantic isomorphism 207 grammatical ambiguity. For example, the ambiguity of such classic examples as: (1) old men and women is plausibly accounted for by saying that its two interpretations "men who are old and women" "old men and old women" reflect a difference of grammatical structure which matches semantic structure. Under one interpretation, represented in (2), 'old' is first combined with 'men' (by a rule of adjectival modification) and, then, the resultant composite expression 'old men' is combined with 'women' (by means of the co-ordinating conjunction and), so that semantically, as well as grammatically, 'old' applies to 'men', but not to 'women': i.e., 'men', but not 'women', is both grammatically and semantically within the scope of 'old'. (We have already met the notion of scope in relation to negation and interrogativity: see 6.5,6.7.) Under the other interpretation, (3), the grammatical rules can be thought of as having operated in the reverse order, so that 'old' applies to the composite expression 'men and women': i.e., the whole phrase 'old men and women' is grammatically and semantically within the scope of 'old'. Grammatical ambiguity of this kind - so-called immediate-constituent or phrase-structure ambiguity - can be handled in many different, but in this respect descriptively equivalent, systems of grammatical analysis; and it is relatively easy to match the grammatical rules of adjectival modification and phrasal coordination (however they are formalized) with rules of semantic interpretation. The question is whether the degree of correspondence, or iso- morphism, between grammatical and semantic structure is always as high as this. Many formal semanticists have assumed that it is and have used the so-called rule-to-rule hypothesis to guide their research. This may be formulated, for our pur- poses, non-technically as follows: (i) every rule of the grammar (and more particularly every syntactic rule) can be associated

208 The formalization of sentence-meaning with a semantic rule which assigns an interpretation to the composite expression which is formed by the grammatical rule in question; and (ii) there are no semantically vacuous grammatical rules. The problem is that it is not usually as clear as it is in the case of (1) that correspondence between grammatical and semantic structure in natural languages is a matter of theory-neutral and empirically determinable fact. Those scholars who subscribe to the so-called rule-to-rule hypothesis are subscribing to a particularly strong version of the principle of compositionality. To be compared with the rule-to-rule hypothesis, which can be seen as a methodological principle adopted by certain formal semanticists to guide them in their research, is the traditional methodological principle of saving the appearances — being duly respectful of the phenomena — which I have invoked on several occasions. A classic case of violating the principle of saving the appearances was Russell's (1905) analysis of the prepositional content of grammatically simple (one-clause) sentences containing noun-phrases introduced by the definite article, such as (4) 'The King of France is bald', whose logical form, under Russell's analysis, turned out to be a composite (three-clause) structure, for two of whose (conjoined) component propositional structures (one containing the existential quantifier and the other the operator of identity) there is no syntactic support. One of the things about Montague's work that attracted linguists was that it brought the logical form of (the propositional content of) many such sentences of English and other natural languages into closer correspondence with their apparent syntactic structure. In the account of formal linguistic semantics that is given in this chapter, I will begin by considering two of the best-known approaches to the problem of determining the compositional function (whatever it is) which assigns sense to the lexically composite expressions of natural languages. I will do so at a very gen-. eral level, and I will restrict my treatment to what is uncontroversially a matter of propositional content. The two 7.3 Deep structure and semantic representations 209 approaches to be considered in the following sections of this chapter are the Katz-Fodor approach and what might be described as classical Montague grammar. I have added a section on possible worlds. The purpose of this is twofold. In the context in which it occurs, it is intended primarily to provide rather more background, philosophical and linguistic, than is usually given in textbook treatments of formal semantics for the particular notion of intensionality that has been developed by Montague and his followers. But it will also serve the more general purpose of raising two questions which have been much discussed (and left unresolved) in the past and have been begged, rather than answered, in much recent work in linguistic semantics, both formal and non-formal: (1) Do all natural languages have the same semantic structure? (2) Do all natural languages have the same descriptive and expressive power? Formal semantics may not be able to provide an answer to either of these two questions, but it has clarified some of the issues. 7.3 DEEP STRUCTURE AND SEMANTIC REPR ESEN TATIONS What I will refer to as the Katz-Fodor theory of sentence-meaning is not generally described as a theory of formal semantics, but I will treat it as such. It originated with a paper by J.J. Katz and J. A. Fodor, 'The structure of a semantic theory', first published in 1963. The theory itself was subsequently modified in various ways, notably by Katz, and has given rise to a number of alternatives, which I will not deal with here. Indeed, I will not even attempt to give a full account of the Katz-Fodor theory in any of its versions. I will concentrate upon the following four notions, which have been of historical importance, and are of continuing relevance: deep structure, semantic representations, projection-rules and selection-restrictions. In this section we shall be concerned with the first two of these four notions, which are of more general import than the other two and, though they may now be obsolete in their original form, have their correlates in several present-day theories of formal semantics.

210 The formalization of sentence-meaning The Katz Fodor theory is formalized within the framework of Chomskyan generative grammar. It was the first such theory of semantics to he proposed, and it played an important part in the development of the so-called standard theory of transformational-generative grammar, which Chomsky outlined in Aspects (1965). I will treat it as an integral part of the Aspects theory, even though, as it was first presented in 1963, it was associated with a slightly modified version of the earlier, Syntactic Structures (1957), model of transformational-generative grammar. Looked at from a more general, historical, point of view, the Katz-Fodor theory can be seen as the first linguistically sophisticated attempt to give effect to the principle of compositionality. Traditional grammarians had for centuries emphasized the interdependence of syntax and semantics. Many of them had pointed out that the meaning of a sentence was determined partly by the meaning of the words it contained and partly by its syntactic structure. But they had not sought to make this point precise in relation to a generative theory of syntax - for the simple reason that generative grammar itself is of very recent origin. As I have said, I will discuss the Katz-Fodor theory, not in its One advantage of operating with the classical notion of deep structure, in a book of this kind, is that it is more familiar to non-specialists than any of the alternatives. Another is that it is simple to grasp and has been widely influential. What will be said about projection-rules and selection-restrictions in the fol-

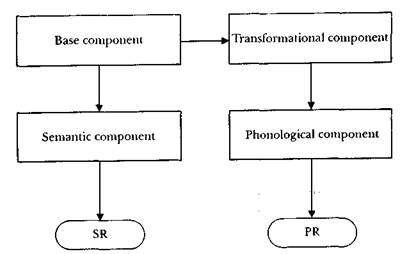

7.3 Deep structure and semantic representations 211 lowing section is not materially affected by the adoption of one view of deep structure rather than another, or indeed by the abandonment of the notion of deep structure altogether. It is also worth emphasizing that, even if the classical notion of deep structure can no longer be justified on purely syntactic grounds, something like it, which (borrowing and adapting a Syntactic Structures term) I am calling the sentence-kernel,might well be justifiable on partly syntactic (or morphosyntactic) and partly semantic grounds (see section 7.2). The significance of this point will be explained as we proceed. According to the standard theory of transformational grammar, every sentence has two distinct levels of syntactic structure, linked by rules of a particular kind called transformations. These two levels are deep structure and surface structure. They differ formally in that they are generated by rules of a different kind. For our purposes the crucial point is that deep structure is more intimately connected with sentence-meaning than surface structure is. Surface structure, on the other hand, is more intimately connected with the way the sentence is pronounced. Omitting all but the bare essentials, we can represent the relation between syntax, semantics and phonology, dia-grammatically, as in Figure 7.1. With reference to this diagram, we can see that the grammar (in the broadest sense of the term) comprises four sets of rules, which, operating as an integrated system, puts a set of phonological representations (PR) into correspondence with a set of semantic representations (SR). What has just been said is often expressed, loosely and non-technically, by saying that the grammar is a system of rules which relates sound and meaning. But it is important to realize that this is indeed a very loose way of making the point; and, as experience has shown, it has led to a good deal of confusion among students and non-specialists. This point is worth developing in some detail. Sound is external to the language-system, and independent of it; sound is the physical medium in which language-utterances (as products of the use of the language-system) are, normally or naturally, realized (and externalized) in speech; considered from a psycholinguistic (and neuropsychological) point of view, 212 The formalization of sentence-meaning phonological representations can be thought of as part of the competence which underlies speech; spoken forms can, however, be transcribed into another medium as written forms, and conversely; the central and essential part of a language - its grammar and associated lexicon - is therefore, in principle, independent of its phonological system. Meaning, on the other hand, is not a medium (physical or non-physical) in which a language is realized. One can argue about the psychological or ontological status of meaning; one can argue as to whether the notion that meaning exists, or can exist, independently of the existence of language-systems (or, more generally, of semiotic systems, including languages) is justifiable; but whatever view we take on such questions, there can be no doubt that the relation between meaning and the language which encodes it is different from the relation between sound and the language which can be realized in it. Neither the use of

Figure 7.1 The standard theory of transformational grammar. The deep structure of a sentence is the output of the base component and the input to both the transformational component and the semantic component; the surface structure of a sentence is the output of the transformational component and the input to the phonological component. 'PR' stands for'phonological representation' and 'SR' for 'semantic representation'. 7.3 Deep structure and semantic representations 213 the term 'representation' in both semantics and phonology nor the input-output symmetry of the left-hand and right-hand sides of the diagram in Figure 7.1 should be allowed to obscure this difference. So much, then, for phonological representations and, for the moment, semantic representations. The base component, it should be noted, contains, not only the non-transformational, categorial,rules of syntax, for the language in question, but also its lexicon,or dictionary. And the lexicon provides for each lexeme in the language all the syntactic, semantic and phonological information that is necessary to distinguish that lexeme from others and to account for its occurrence in well-formed sentences. The base component, then, generates a set of deep structures, and the transformational component converts each of these into one or more surface structures. I said earlier that deep structure is more intimately connected with meaning, and surface structure with pronunciation. Figure 7.1 makes this point clear by means of the arrows which link the several components of the grammar. All the information required by the semantic component is supplied by the base, and therefore is present in the deep structure of sentences; all the information required by the phonological component is present in the surface structures that result from the operation of transformational rules. As far as the relation between syntax and semantics is concerned, Figure 7.1 expresses the famous principle that transformations do not affect meaning;there is no arrow leading from the transformational to the semantic component. This principle is intuitively appealing, provided that 'meaning' is interpreted as referring to propositional content: it is less so, if (i) sentence-meaning is held to include thematic meaning and what is encoded in difference of mood and sentence-type and (ii) corresponding sentences which differ grammatically in thematic structure, mood or sentence-type are held to be transformationally related and to share the same deep structure (see Chapter 6). The principle that transformations do not affect meaning implies that any two, or more, sentences that have the same deep structure will necessarily have the same meaning. 214 The formalization of sentence-meaning For example, corresponding active and passive sentences (which differ in thematic structure), such as 'The dog bit the postman' 'The postman was bitten by the dog',

have often been analysed as having the same deep structure: see Figure 7.2. (This is not how Chomsky treated them in Aspects, but for present purposes that is irrelevant.) Most such pairs of active and passive sentences (apart from sentences containing what a logician would describe as the natural-language equivalents of quantifiers) are truth-conditionally equivalent, and therefore have the same prepositional content. Arguably, however, they differ in thematic meaning, in much the same way that''I have not read this book', 'This book I have not read', etc. differ from one another in thematic meaning: see Chapter 7.4 Projection-rules and selection-restrictions 215 6, examples (l)-(4) and (5)-(6). For syntactic reasons that do not concern us here, sets of sentences such as 'I have not read this book', 'This book I have not read', etc. are given the same deep structure in the standard theory, whereas corresponding active and passive sentences are not. But this fact is irrelevant in the context of the present account. So too is the fact that much of the discussion by linguists of the relation between syntax and semantics has been confused, until recently, by the failure to distinguish propositional content from other kinds of sentence-meaning. The point that is of concern to us is that some sentences will have the same deep structure, though they differ quite strikingly in surface structure, and that all such sentences must be shown to have the same propositional content. This effect is achieved, simply and elegantly, by organizing the grammar in such a way that the rules of the semantic component operate solely upon deep structures. 7.4 PROJECTION-RULES AND SELECTION-RESTRICTIONS We now come to the notions of projection-rules and selection-restrictions as these were formalized by Katz and Fodor (1963) within the framework of Chomskyan transformational-generative grammar. In the Katz-Fodor theory the rules of the semantic component are usually called projection-rules. In the present context, they may be identified with what are more generally referred to nowadays as semantic rules. They serve two purposes: (i) they distinguish meaningful from meaningless sentences; and (ii) they assign to every meaningful sentence a formal specification of its meaning or meanings. I will deal with each of these two purposes separately. We have already seen that the distinction between meaningful and meaningless sentences is not as clear-cut as it might appear at first sight (see 5.2). And I have pointed out that, in the past, generative grammarians have tended to take too restricted a view of the semantic well-formedness of sentences. In this section we are concerned with the formalization of semantic 216 The formalization of sentence-meaning ill-formedness (meaninglessness), on the assumption that, oven though it may not be as widespread as is commonly supposed, it does in fact exist. Our assumption, more precisely, is that in English and in other natural languages, there are some grammatically well-formed, but semantically ill-formed, sentences (though not as many as linguists tended to assume in the classical period of Chomskyan transformational-generative grammar). The Katz-Fodor mechanism for handling semantic ill-formedness is that of selection-restrictions. These are associated with particular lexemes and are therefore listed, in what we may think of as dictionary entries, in the lexicon. They tell us, in effect, which pairs of lexemes can combine with one another meaningfully in various grammatical constructions. For example, they might say that the adjective 'buxom' can modify nouns such as 'girl', 'woman', 'lass', etc., but not 'boy', 'man', 'lad', etc., that the verb 'sleep' can take as its subject nouns such as 'boy', 'girl', 'cat', etc. (or, rather noun-phrases, with such nouns as their principal constituent), but not such nouns as 'idea' or 'quadruplicity'; and so on. If the selection-restrictions are violated, the projection-rules will fail to operate. Consequently, they will fail to assign to the semantically ill-formed sentence a formal specification of its meaning - thereby marking the sentence as meaningless and (provided that this information is preserved in the output) indicating in what way the sentence is semantically ill-formed. A further task of the selection-restrictions, operating in conjunction with the projection-rules, is to block certain interpretations as semantically anomalous, while allowing other interpretations of the same phrases and sentences as semantically acceptable. For example, in some dialects or registers of English, the word 'housewife' is polysemous: in one of the senses ("housewife1") it denotes a woman who keeps house; in another ("housewife2') it denotes a pocket sewing-kit. Many phrases in which 'housewife' is modified by an adjective ('good housewife', 'beautiful housewife', etc.) will be correspondingly ambiguous. But 'buxom housewife', presumably, will not, since "housewife2', unlike "housewife1", cannot combine with the meaning of 'buxom'. In general, then, the selection-restrictions will tend 7.4 Projection-rules and selection-restrictions 217 to cut clown the number of interpretations assigned to lexically composite expressions. In fact, the failure to assign any interpretations at all to a sentence, referred to in the previous paragraph, can be seen as the limiting case of this process. The rules select from the meanings of an expression those, and only those, which are compatible with the (sentence-internal) context in which it occurs. The Katz-Fodor theory of sentence-meaning is formulated within the framework of componential analysis (see 4.2). For example, instead of listing, in the lexical entry for 'buxom', all the other lexemes with which it can or cannot combine, the theory will identify them by means of one or more of their sense-components. It might say (in an appropriate formal notation) that 'buxom' cannot be combined, in semantically well-formed expressions, with any noun that does not have as part of its meaning the sense-components human and, let us assume, female. As we have seen, componential analysis runs into quite serious problems, if it is pushed beyond the prototypical, or focal, meaning of expressions. It is for this reason that most of the textbook examples used by linguists to illustrate the operation of Katz-Fodor selection-restrictions are empirically suspect. But we are not concerned, at this point, with the validity of componential analysis. Nor is it necessary to take up once again the problem of drawing a distinction between contradiction and semantic ill-formedness. My purpose has been simply to explain what selection-restrictions are and how they are formalized in the Katz-Fodor theory. It is important, however, to say something here about cate-gorial incongruity,which was mentioned at the end of Chapter 5; and what I have to say will be relevant to other theories of formal semantics. The term 'categorial incongruity' is intended to refer to a particular kind of semantic incompatibility which, in particular languages, is intimately associated with grammatical, more precisely syntactic, ill-formedness. It may be introduced by means of the following examples: (7) 'My friend existed a whole new village' and 218 The formalization of sentence-meaning (8) 'My friend frightened that it was raining'. Arguably, although I have represented them as sentences, each of them is both grammatically and semantically ill-formed. Their ungrammaticality can be readily accounted for by saying that 'exist' is an intransitive verb (and therefore cannot take an object) and that 'frighten', unlike 'think', 'say', etc., cannot occur with a that-clause as its object. (Such examples are handled by Chomsky in Aspects in terms of what he calls strict subcategor-ization.) The fact that they do not make sense - that they have no prepositional content - can be explained by saying that it is inherent in the meaning of 'exist' that it cannot take an object, and that it is inherent in the meaning of 'frighten' that it cannot take as its object an expression referring to such abstract entities as facts or propositions. But which, if either, of these two explanations - syntactic or semantic — is correct? The question is wrongly formulated. It makes unjustified assumptions about the separability of syntax and semantics and ignores the fact that, although natural languages vary considerably as to what they grammaticalize (or lexicalize), there is, in all natural languages, some degree of congruence between semantic (or ontological) categories and certain grammatical categories, such as the major parts of speech, gender, number, or tense. Whether one accounts for categorial incongruity by means of the syntactic rules of the base component or alternatively by means of the blocking, or filtering, mechanism of the projection-rules is, of itself, a technical issue of no empirical import. What is important is that, whatever treatment is adopted, the details of the formalization should distinguish cases of categorial incongruity from (a) cases of contradiction and from (b) what are more generally handled in terms of selection-restrictions. Contradictory propositions are meaningful, but necessarily false. Expressions whose putative semantic ill-formedness results from the violation of selection-restrictions can often be given a perfectly satisfactory interpretation if one is prepared to make not very radical adjustments to one's assumptions about the nature of the world. Categorially incongruous expressions are 7.4 Projection-rules and selection-restrictions 219 meaningless and they cannot be interpreted by making such minor ontological adjustments. (A classic Chomskyan example of a sentence containing a mixture of contradictory and catego-rially incongruous expressions is 'Colourless green ideas sleep furiously': see 5.3). These boundaries may be difficult to draw in respect of particular examples. But the differences are clear enough in a sufficient number of cases for the distinctions themselves to be established. Let us now return to the Katz-Fodor projection-rules. We have seen how they distinguish meaningful sentences from at least one class of meaningless, or allegedly meaningless, sentences. They also have to assign to every semantically well-formed sentence a formal specification of its meaning or meanings. Such specifications of sentence-meaning are described as semantic representations. It follows from what has been said so far that a sentence will have exactly as many semantic representations as it has meanings (the limiting case being that of meaningless sentences, to which the projection-rules will assign no semantic representation at all). It also follows that sentences with the same deep structure will have the same semantic representation. The converse, however, does not follow; in the standard theory of transformational-generative grammar, sentences that differ in deep structure may nevertheless have the same meaning. This is a consequence of the existence of synonymous, but lexically distinct, expressions (see 2.3) and of the way in which lexicalization is handled in the standard theory. We may simply note that this is so, without going into the details. But what precisely are semantic representations? And how are they constructed by the projection-rules? These two questions are, of course, interdependent (by virtue of the principle of compositionality). A semantic representation is a collection, or amalgamation, of sense-components. But it is not merely an unstructured set of such components. As we saw in section 4.3, it is not generally possible to formalize the meaning of individual lexemes compositionally in set-theoretic terms. It is even more obviously the case that sentence-meaning cannot be formalized I in this way. If a semantic representation were nothing more

220 The formalization of sentence-meaning than a set of sense-components (or semantic markers, in Katz-Fodor terminology), any two sentences containing exactly the same lexemes would be assigned the same semantic representation. For example, not only 'The dog bit the postman' 'The postman was bitten by the dog', (9) 'The postman bit the dog' (and each of indefinitely many pairs of sentences like them), would be assigned the same semantic representation as one another. This is patently incorrect. What is required is some for-malization of semantic representations that will preserve the semantically relevant syntactic distinctions of deep structure. It is probably fair to say that in the years that have passed since the publication of 'The structure of a semantic theory' by Katz and Fodor little real progress has been made along these lines. The formalization has been complicated by the introduction of a variety of technical devices. But no general solution has been found to the problem of deciding exactly how many projection-rules are needed and how they differ formally one from another. And most linguists who are interested in either generative grammar or formal semantics are now working within a quite different theoretical framework. One reason why this is so, apart from developments in Chomskyan and post-Chomskyan generative grammar since the mid-1970s, is that the whole concept of semantic representations has been strongly criticized, on two grounds, by logicians and philosophers. First of all, they have pointed out that Katz-Fodor semantic representations make use of what is in effect a formal language and that the vocabulary-units of this language (conventionally written in small capitals, as in Chapter 4) stand in need of interpretation, just as much as do the natural languages whose 7.5 Montague grammar 221 semantic structure the formal language interprets. This objection may be countered, more or less plausibly, by saying that the formal language in question is the allegedly universal language of thought, which we all know by virtue of being human and which therefore does not need to be interpreted by relating its lexemes to entities, properties and relations in the outside world. The second challenge to the notion of semantic representations comes from those who argue that they are unnecessary; that everything done satisfactorily by means of semantic representations can be done no less satisfactorily without them -by means of rules of inference operating in conjunction with meaning-postulates. This approach has the advantage that it avoids many of the difficulties, empirical and theoretical, associated with componential analysis. 7.5 MONTAGUE GRAMMAR What is commonly referred to as Montague grammar is a particular approach to the analysis of natural languages initiated by the American logician Richard Montague in the late 1960s. During the 1970s, it was adopted by many linguists, who saw it (as did Montague himself) as a semantically more attractive alternative to Chomskyan transformational-generative grammar. (Montague himself died when still quite young, in 1971, and did little more than lay the foundations of what linguists inspired by his ideas called 'Montague grammar'.) In this context, 'grammar' is to be understood as covering both syntax and semantics. Some of the differences between Montague grammar and the Katz-Fodor theory are a matter of historical accident. Montague's work is more firmly rooted in logical semantics than the Katz-Fodor theory is and gives proportionately less consideration to many topics that have been at the forefront of linguists' attention. In fact, 'grammar' for Montague included only part of what the standard theory of generative grammar sets out to cover. There is nothing in Montague's own work about phonological representation or inflection. The Katz-Fodor theory, on 222 The formalizatwn of sentence-meaning the other hand, finds its place (as Figure 7.1 in section 7.3 indicates) within a more comprehensive theory of the structure of languages, in which semantics and phonology (and indirectly inflection) are on equal terms. Linguists who have adopted Montague grammar have seen it as being integrated, in one way or another, with an equally comprehensive generative, though not necessarily Chomskyan, theory of the structure of natural languages, covering not only syntax (and morphology), but also phonology. Having said this, however, I must repeat one of the points made in section 7.3: phonology, unlike semantics, is only contingently associated with grammar (and, more particularly, syntax) in natural languages. The fact that Montague, like most logical semanticists, showed little interest in phonology (and morphology) is, therefore, neither surprising nor reprehensible. More to the point is the status of transformational rules, on the one hand, and of componential analysis, or lexical decomposition, on the other. Montague himself did not make use of transformational rules. There were at least three reasons for this. First, the syntactic rules that he used in what we may think of as the base component of his grammar are more powerful than Chomskyan phrase-structure rules. Second, he was not particularly concerned to block the generation of syntactically ill-formed strings of words, as long as they could be characterized as ill-formed by the rules of semantic interpretation. Third, he had a preference for bringing the semantic analysis of sentences into as close a correspondence as possible with what transformationalists would describe as their surface structure. There is therefore no such thing as deep structure in Montague's own system. But this is not inherent in Montague grammar as such; and, during the 1970s, a number of linguists made proposals for the addition of a transformational component to the system. At the same time, it must also be noted, as we shall see, that the role of transformational rules was successively reduced in Chomskyan transformational-generative grammar in what we now think of as the post-classical period. By the end of the 1970s, if not earlier, the view that Montague took of the relation between syntax and semantics no longer seemed as eccentric 7.5 Montague grammar 223 and as badly motivated to generative grammarians as it may have done initially. And there are now, in any case, many different, more or less Chomskyan, systems of generative grammar, other than Chomsky's own system (which has been continually modified over the years and is now strikingly different from the standard, or classical, Aspects system). No one of these enjoys supremacy; and no linguist, these days, could sensibly think that formal semanticists have a straight choice between two, and only two, rival systems of linguistic analysis and description, when it comes to the integration of semantics and syntax. As for componential analysis (or lexical decomposition), much the same remarks can be made here too. Montague grammar as such is not incompatible, in principle, with the decomposition, or factorization, of lexical meaning into sense-components. Indeed, some linguists have made proposals for the incorporation of rules for lexical decomposition within the general framework of Montague grammar. But, once again, as I have mentioned in the previous section and in Chapter 4, componential analysis is not as widely accepted by linguists now as it was in the 1960s and early 1970s. The comparison of Chomskyan generative grammar with Montague grammar is complicated by the fact that, as I have said, some of the differences between them derive from purely historical circumstances. Most earlier presentations of Montague grammar were highly technical and took for granted a considerable degree of mathematical expertise and some background in formal logic. The situation has improved recently in that there are now good textbook presentations that are designed specifically for students of linguistic semantics. As for textbook accounts of Chomskyan generative grammar (of which there are many), most of these, whether technical or non-technical, fail to draw the distinction between what is essential to it and what is contingent and subject to change. They also fail to distinguish between generative grammar, as such, and generativism or what is commonly referred to nowadays as the generative enterprise. Montague grammar is of its nature a very technical subject (just as Chomskyan generative grammar is). It would be foolish 224 The formalization of sentence-meaning to encourage the belief that any real understanding of the details can be achieved unless one has a considerable facility in mathematical logic. However, it is not the details that are of interest to us here. My purpose is simply to explain, non-technically, some of the most important features of Montague grammar, in so far as they are relevant to the formalization of sentence-meaning and are currently exploited in linguistic semantics. In doing so, I will concentrate upon such features as may be expected to have an enduring influence, independently of current or future developments in linguistics and logic, and in the philosophy and psychology of language. Montague semantics - the semantic part, or module, of a Montague grammar - is resolutely truth-conditional. Its applicability is restricted, in principle, to the prepositional content of its sentences. Just how big a restriction this is judged to be will, of course, depend upon one's evaluation of the points made in the preceding chapter. Most of the advocates of Montague semantics have no doubt been committed, until recently at least, to the view that the whole of sentence-meaning is explicable, ultimately, in terms of prepositional content. It has long been recognized, however, as was noted in the preceding chapter, that non-declarative sentences, on the one hand, and non-indicative sentences, on the other, are problematical from this point of view. Various attempts have been made to handle such sentences within the framework of Montague grammar. But so far none of these has won universal acceptance, and all of them would seem to be vulnerable to the criticisms directed against the truth-conditional analysis of non-declarative and non-indicative sentences in Chapter 6. In what follows we shall be concerned solely with propositional content. Unlike certain other truth-conditional theories, Montague semantics operates, not with a concept of absolute truth, but with a particular notion of relative truth: truth-under-an-interpretation or, alternatively, in the technical terminology of model theory, truth-in-a-model. (I will say something presently about the sense in which the initially puzzling term 'model' is being employed here.) What model theory does in effect (though it is not usually explained in this way) is to- 7.5 Montague grammar 225 formalize the distinction that is drawn in this book between propositions and propositional content. As used by Montague and his followers (who were in turn drawing upon the work of Carnap and others), it does this by drawing upon the distinction between extension and intension and relating this to a particular notion of possible worlds,which originated (as we saw in section 4.4) with Leibniz. Model theory is by no means restricted to the use that is made of it by Montague: it is much more general than that. But for the moment we can limit the discussion to Montague's version of model theory, since this is so far the one most familiar to linguists. The traditional distinction between extension and intension has been exploited in a variety of ways in modern logic and formal semantics, so that the term 'intensional' (not to be confused with its homophone 'intentional') has a quite bewildering range of historically interconnected uses. We shall be concerned only with those uses that are of immediate relevance. We may begin (following Carnap) by identifying Frege's distinction between reference ('Bedeutung') and sense ('Sinn') with the distinction between extension and intension. (We should note that, as was mentioned earlier, Frege's word for reference -which he did not distinguish from denotation, as he did not distinguish sentences from either utterances or propositions - is the ordinary German word for meaning.) It is generally agreed nowadays that sense, rather than reference, is what is encoded in the sentences of natural languages, and this is what the German word 'Bedeutung' would normally be used for. We can now go on to apply the extension/intension distinction to the analysis of sentence-meaning, saying that the sense, or intension, of a sentence is its propositional content, whereas its reference, or extension, is its truth-value (on particular occasions of utter- ance). Most people at first find it strange that Frege, and follow- ing him many, though not all, formal semanticists, should have taken sentences (or propositions) to refer to truth or falsity, rather than to the situations that they purport to describe. But this view of the matter has certain formal advantages with respect to compositionality. 226 The formalization of sentence-meaning The next step is to invoke the notion of possible worlds. As we saw earlier, necessarily true (or false) propositions are propositions that are true (or false) in all possible worlds. The notion has also been applied, in an intuitively plausible way, in the definition of descriptive synonymy, as follows: expressions are descriptively synonymous if, and only if, they have the same extension in all possible worlds. Since expressions are descriptively synonymous if, and only if, they have the same sense (which we have identified with their intension), it follows that the intension of an expression is either its extension in all possible worlds or some function which determines its extension in all possible worlds. The second of these alternatives is the one that is adopted in Montague grammar. The intension of an expression is defined to be a function from possible worlds to extensions. But what does this mean? The answer that I will give to this question is somewhat different from the answer that is given in standard accounts of formal semantics, but it is an answer that is faithful to the spirit of Montague semantics and philosophically defensible. My deliberately non-technical explanation of the basic notions of Montague's version of model-theoretic possible-worlds semantics is couched as far as possible in terms of the notions and distinctions that have been explained and adopted in earlier chapters. 7.6 POSSIBLE WORLDS Leibniz introduced the notion of possible worlds for primarily theological purposes, arguing that God, being omniscient (and beneficent), would necessarily actualize the best of all possible worlds and, though omnipotent, was none the less subject in his creativity to the constraints of logic: he could create, or actualize, only logically possible worlds. As exploited by modern logicians, the notion of possible worlds has, of course, been stripped of its theological associations, and it has been converted into a highly technical, purely secular and in itself non-metaphysical, concept. But some knowledge of its philosophical and theologi- cal origins may be helpful (especially when it comes to the use 7.6 Possible worlds 227 that is made of the notion of possible worlds in epistemic and deontic logic). Hence this brief philosophical interlude. Every natural language, let us assume, provides those who are competent in it with (a) the means of identifying the world that is actual at the time of speaking - the extensional world -and distinguishing it from past and future worlds, and (b) the means of referring to individual entities and sets of entities, on the one hand, and to substances, on the other, in whatever world has been identified. We may refer to whatever means is used to identify temporally distinct worlds (tense, adverbs of time, etc.) as an index - more precisely, a temporal index - to the world in question. I shall have more to say about this in Chapter 10: here I will simply draw readers' attention to the connexion between the term 'index', as I have just used it, and 'indexicality'. An alternative to 'index', in this sense, is 'point of reference': possible worlds are identified from a particular point ofreference. Granted that one can identify the world that is explicitly or implicitly identified, how does one know what is being referred to by the expression that is used, when a sentence is uttered? For example, how does one know what 'those cows' refers to in the utterance of (10) 'Those cows are pedigree Guernseys'? The traditional answer, as we have seen, is that one knows the concept "cow" and that this, being the intension (or sense) of 'cow', determines its extension. (One also needs to be able to interpret the demonstrative pronoun 'that' and the grammatical category of plurality. But let us here assume - and it is a not inconsiderable assumption - that the meaning of 'that' and plurality, not to mention the grammatical category of tense, can be satisfactorily handled in model-theoretic terms.) Concepts are often explained in terms of pictures or images, as in certain versions of the ideational theory of meaning (see 1.7). But we can now think of them more generally, as functions (in the mathematical sense): that is, as ru

|