CHAPTER 4 1 страница

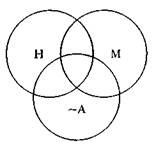

The structural approach 4.0 INTRODUCTION As we saw in the last chapter, words cannot be defined independently of other words that are (semantically) related to them and delimit their sense. Looked at from a semantic point of view, the lexical structure of a language - the structure of its vocabulary - can be regarded as a network of sense-relations:it is like a web in which each strand is one such relation and each knot in the web is a different lexeme. The key-terms here are 'structure' and 'relation', each of which, in the present context, presupposes and defines the other. It is the word 'structure' (via the corresponding adjective 'structural') that has provided the label - 'structuralism' -which distinguishes modern from pre-modcrn linguistics. There have been, and are, many schools of structural linguistics; and some of them, until recently, have not been very much concerned with semantics. Nowadays, however, structural semantics (and more especially structural, lexical semantics) is as well established everywhere as structural phonology and structural morphology long have been. But what is structural semantics? That is the question we take up in the following section. We shall then move on to discuss two approaches to the task of describing the semantic structure of the vocabularies of languages in a precise and systematic way: componential analysis and the use of meaning-postulates. Reference will also be made, though briefly, to the theory of semantic fields (or lexical fields). Particular attention will be given to componential 4.1 Structural semantics 103 analysis, because this has figured prominently in the recent literature of lexical semantics. As we shall see, it is no longer as widely supported by linguists as it was a decade or so ago, at least in what one might think of as its classical formulation. The reasons why this is so will be explained in the central sections of this chapter. It will also be shown that what are usually presented as three different approaches to the description of lexical meaning - componential analysis, the use of meaning postulates and the theory of semantic fields - are not in principle incompatible. In our discussion of lexical structure in this chapter, we shall 4.1 STRUCTURAL SEMANTICS Structuralism, as we saw in the preceding chapter, is opposed to atomism (3.3). As such, it is a very general movement, or attitude, in twentieth-century thought, which has influenced many academic disciplines. It has been especially influential in the social sciences and in linguistics, semiotics and literary criticism 104 The structural approach 'and in various interdisciplinary combinations of two or all three of these). The brief account of structural semantics that is given here is restricted to what might be described, more fully, as structuralist linguistic semantics: i.e., to those approaches to linguistic semantics (and, as we shall see, there are several) that are based on the principles of structuralism. It should be noted, however, that structural semantics, in this sense, overlaps with other kinds of structural, or structuralist, semantics: most notably, in the post-Saussurean tradition, with parts of semiotic and literary semantics. Here, as elsewhere, there is a certain artificiality in drawing the disciplinary boundaries too sharply. The definition that I have given of structural semantics, though deliberately restricted to linguistic semantics, is nevertheless broader than the definition that many would give it and covers many approaches to linguistic semantics that are not generally labelled as 'structural semantics' in the literature. First of all. for historical reasons the label 'structural semantics' is usually limited to lexical semantics. With historical hindsight one can see that this limitation is, to say the least, paradoxical. One of the most basic and most general principles of structural linguistics is that languages are integrated systems, the component subsystems for levels; of which - grammatical, lexical and phonological - are interdependent. It follows that one cannot sensibly discuss the structure of a language's vocabulary (or lexicon) without explicitly or implicitly taking account of its grammatical structure. This principle, together with other, more specific, structuralist principles, was tacitly introduced (without further development) in Chapter 1 of this book, when I explained the Saussurean distinction between 'langue' and 'langage' (including 'parole') and, despite the organization of the work into separate parts, will be respected throughout. The main reason why the term 'structural semantics' has generally been restricted to lexical semantics is that in the earlier part of this century the term 'semantics' (in linguistics) was similarly restricted. This does not mean, however, that earlier generations of linguists were not concerned with what we now recognize as non-lexical, and more especially grammatical, semantics. On the contrary, traditional grammar - both syntax 4.1 Structural semantics 105 and morphology, but particularly the former - was very definitely and explicitly based on semantic considerations: on the study of what is being handled in this book under the rubric of 'sentence-meaning'. But the meaning of grammatical categories and constructions had been dealt with, traditionally, under 'syntax', 'inflection' and 'word-formation' (nowadays called 'derivation'). Structuralism did not have as widespread or as early an effect on the study of meaning, either lexical or non-lexical, as it did on the study of form (phonology and morphology). Once this effect came to be discernible (from the 1930s), structural semantics should have been seen for what it was: lexical semantics within the framework of structural linguistics. Some, but not all, schools of structural linguistics saw it in this way. And after the Second World War all the major schools of linguistics proclaimed their adherence to what I have identified above as the principal tenet of structuralism. We now come to a second historical reason why the term 'structural semantics' has a much narrower coverage in the literature, even today, than it should have and - more to the point - why the structural approach to semantics, identified as such, is still not as well represented as it should be in most textbooks of linguistics. By the time that the term 'structural semantics' came to be widely used in Europe (especially in Continental Europe) in the 1950s, the more general term 'structural linguistics' had become closely associated in the United States with the particularly restricted and in many ways highly-untypical version of structuralism known as Bloomfieldian or post-Bloomfieldian linguistics. One of the distinguishing (and controversial) features of this version of structural linguistics was its comparative lack of interest in semantics. Another was its rejection of the distinction between the language-system and either the use of the system (behaviour) or the products of the use of the system (utterances). The rehabilitation of semantics in what one may think of as mainstream American linguistics did not come about until the mid-1960s, in the classical period of Chomskyan generative grammar, and, when this happened, as we shall see in Part 3, it was sentence-meaning rather than lexical meaning that was of particular concern to generative 106 The structural approach grammarians, on the one hand, and to formal semanticists, on the other., Although the Bloomfieldian (or post-Bloomfieldian) school'of linguistics was comparatively uninterested in, and in certain instances dismissive of, semantics, there was another tradition in the United States, strongly represented among anthropological linguists in the 1950s, which stemmed from Edward Sapir, rather than Leonard Bloomfield, and was by no means uninterested in semantics. In other respects also, this tradition was much closer in spirit to European structuralism. Sapir was mentioned above in connexion with what is commonly referred to as the Sapir—Whorf hypothesis:, the hypothesis that every language is, as it were, a law unto itself; that each language has its own unique structure of grammatical and lexical categories, and creates its own conceptual reality by imposing this particular categorial structure upon the world of sensation and experience (3.3). When I mentioned the Sapir—Whorf hypothesis earlier, I noted that there was no necessary connexion between this kind of linguistic relativism (or anti-universalism) and the essential principles of structuralism. Not only is this so, but it is, arguable that Sapir himself was not Committed to a strongly relativistic version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Many of his followers were certainly not so committed. Indeed, they were responsible for promoting in the United States'a particular kind of structuralist lexical semantics, componential analysis, one of the features of which was that it operated with a set of atomic components of lexical meaning that were assumed to be universal. As we shall see in Part 3, this was subsequently incorporated in the so-called standard theory of generative grammar in the mid-1960s. As there are many schools of structural linguistics, so there are many schools of structural semantics (lexical and non-lexical). Not all of these will be dealt with, or even referred to, in this book. For reasons that will be explained in the following sections, we shall be concentrating on the approach to lexical semantics that has just been mentioned: componential analysis. This is not a distinguishable school of semantics, but rather a 4.2Componential analysis 107 method of analysis which (with variations which will be pointed out later) is common to several such schools. At first sight, componential analysis, which is based on a kind of atomism, might seem to be incompatible with structuralism. But this is not necessarily so. What really counts is whether the atoms of meaning into which the meanings of words are analysed, or factorized, are thought of as being logically and episte-mologically independent of one another (in the way that logical. atomists like Russell thought the meanings of words were logically and epistemologically independent: 3.2). Some practitioners of componential analysis take this view; others do not. But both groups will tend to emphasize the fact that all the words in the same semantic field are definable in terms of the structural relations that they contract with one another, and they will see componential analysis as a means of describing these relations. It is this emphasis on languages as relational structures which constitutes the essence of structuralism in linguistics. What this means as far as lexical meaning is concerned will be explained in the following sections. As we shall see, looked at, from this point of view, componential analysis in lexical semantics is, as it were, doubly structuralist (in the same way that distinctive-feature analysis in phonology is also doubly structuralist). It defines the meaning of words, simultaneously, in terms of the external, interlexical, relational structures - the semantic fields - in which semanti-cally related and interdefinable words, or word-meanings, function as units and also in terms of the internal, intralexical and as it were molecular, relational structures in which what I am here calling the atoms of word-meaning function as units. 4.2 COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS One way of formalizing, or making absolutely precise, the sense-relations that hold among lexemes is by means of componential analysis. As the name implies, this involves the analysis of the sense of a lexeme into its component parts. It has a long history in philosophical discussions of languages. But it is only recently that it has been employed at all extensively by linguists. 108 The structural approach An alternative term for componcntial analysis is lexical decomposition. Let us begin with a much used example. The words 'boy', 'girl', 'man' and 'woman' all denote hurrian beings. We can therefore extract from the sense of each of them the common factor "human": i.e., the sense of the English word 'human'. Throughout this section, the notational distinction between single and double quotation-marks is especially important: see 1.5.) Similarly, we can extract from "boy" and "man" the common factor "male", and from "girl" and "woman", the common factor "female". As for "man" and "woman", they can be said to have as one of their factors the sense-component "adult", in contrast with "boy" and "girl", which lack "adult" (or. alternatively, contain "non-adult"). The sense of each of the four words can thus be represented as the product of three factors: "man" = "human" x "male" x "adult" "woman" = "human" x "female" x "adult" "boy" = "human" x "male" x "non-adult" "girl" = "human" x "female" x "non-adult" I have deliberately used the multiplication-sign to emphasize the fact that these are intended to be taken as mathematically precise equations, to which the terms 'product' and 'factor' apply exactly as they do in, say, 30 = 2 x 3 x 5. So far so good. Whether the equations we set up are empirically correct is another matter. We shall come to this presently. Actually, sense-components are not generally represented by linguists in the way that I have introduced them. Instead of saying that "man" is the product of "human", "male" and "adult", it is more usual to identify its factors as human, male and adult. This is not simply a matter of typographical preference. By convention, small capitals are employed to refer to the allegedly universal sense-components out of which the senses of expressions in particular natural languages are constructed. Much of the attraction of componential analysis derives from the possibility of identifying such universal sense-components in the lexical structure of different languages. They are frequently 4.2 Componential analysis 109 described as basic atomic concepts in the sense of 'basic' that is dominant in the philosophical tradition (which, as was noted in Chapter 3, does not necessarily correspond with other senses of 'basic'). What then, is the relation between human and "human", between male and "male", and so on? This is a theoretically important question. It cannot be assumed without argument that male necessarily equals, or is equivalent with, "male": that the allegedly universal sense-component male is identical with "male" (the sense of the English word 'male'). And yet it is only on this assumption (in default of the provision of more explicit rules of interpretation) that the decomposition of "man" into male, adult and human can be interpreted as saying anything about the sense-relations that hold among the English words 'man', 'male', 'human' and 'adult'. We shall, therefore, make the assumption. This leaves open the obvious question: why should English, or any other natural language, have privileged status as a metalanguage for the semantic analysis of all languages? We can now develop the formalization a little further. First of all, we can abstract the negative component from "non-adult" and replace it with the negation-operator,as this is defined in standard prepositional logic: '~'. Alternatively, and in effect equivalently, we can distinguish a positive and a negative value of the two-valued variable +/-adult (plus-or-mirius adult), whose two values are +adult and -adult. Linguists working within the framework of Chomskyan generative grammar have normally made use of this second type of notation. We now have as a basic, presumably atomic, component ADULT, together with its complementary -adult. If male and female are also complementary, we can take one of them as basic and form the other from it by means of the same negation-operator. But which of them is more basic than the other, either in nature or in culture? The question is of considerable theoretical interest if we are seriously concerned with establishing an inventory of universal sense-components. It is in principle conceivable that there is no universally valid answer. What is fairly clear, however, is that, as far as the vocabulary of English is concerned, 110 The structural approach it is normally male that one wants to treat as being more general and thus, in one sense, more basic. Feminists might argue, and perhaps rightly, that this fact is culturally explicable. At any rate, there are culturally explicable exceptions: 'nurse', 'secretary', etc., among words that (normally) denote human beings; 'goose', 'duck', and in certain respects 'cow', among words denoting domesticated animals. As for human, this is in contrast with a whole set of what from one point of view are equally basic components: let us call them canine, feline, bovine, etc. They are equally basic in that they can be thought of as denoting the complex defining properties of natural kinds (see 3.3). Earlier, I used the multiplication-sign to symbolize the operation by means of which components are combined. Let me now substitute for this the propositibnal connective1 bf conjunction:'&'. We can then rewrite the analysis of "man", "woman", "boy", "girl" as: (la) "man" = human & male & adult (2a) "woman" = human & ~ male & adult (3a) "boy" = human & male & ~ adult (4a) "girl" = human & ~male& ~ adult And to this we may add: (5) "child";= HUMAN & ~ ADULT in order to make clear the difference between the absence of a component and its negation. The absence of ~male from the representation of the sense of'child' differentiates "child" from "girl". As for 'horse', 'stallion', 'mare', 'foal', 'sheep', 'ram', 'ewe', 'lamb', 'bull', 'cow', 'calf - these, and many other sets of words, can be analysed in the same way by substituting equine, ovine, bovine, etc., as the case may be, for human. The only logical operations utilized so far are negation and conjunction. And. in using symbols for prepositional operators, '~' and '&', and attaching them directly, not to propositions, but to what logicians would call predicates, I have taken for granted a good deal of additional formal apparatus. Some of this will be introduced later. The formalization that I have employed is not the only possible one. I might equally have 4.2 Componential analysis 111 used, at this point, the terminology and notation of elementary set-theory. Everything said so far about the compositional nature of lexical meaning could be expressed in terms of sets and their complements and of the intersection of sets. For example, "boy" = human & male & ~ adult can be construed as telling us that any individual element that falls within the extension of the word 'boy' is contained in the intersection of three sets H, M and ~A, where H is the extension of 'human' (whose intension is HUMAN = "human"), M is the Extension of 'male' and ~A is the complement of the extension of 'adult'. This is illustrated graphically by means of so-called Venn diagrams in Figure 4.1. There are several reasons for introducing these elementary notions of set-theory at this point. First, they are implicit, though rarely made explicit, in more informal presentations of compo-nential analysis. Second, they are well understood and have been precisely formulated in modern mathematical logic; and as we shall see in Part 3, they play an important role in the most influential systems of formal semantics. Finally, they enable us to give a very precise interpretation to the term 'product' when we say that the sense of a lexeme is the product of its components, or factors.

Let me develop this third point in greater detail. I will begin by replacing the term 'product' with the more technical term 'compositional function', which is now widely used in formal

112 The structural approach semantics. To say that the sense of a lexeme (or one of its senses) is a compositional function of its sense-components is to imply that its value is fully determined by (i) the value of the components and (ii) the definition of the operations by means of which they are combined. To say that the sense of a lexeme is a set-theoretic function of its sense-components is to say that it is a compositional function of a particularly simple kind. The notion of compositionality,as we shall see in Part 3, is absolutely central in modern formal semantics. So too is the mathematical sense of the term 'function'. All those who have mastered the rudiments of elementary set-theory at school (or indeed of simple arithmetic and algebra considered from a sufficiently general point of view) will be familiar with the principle of compositionality and with the mathematical concept of a compositional function already, though they may never have met the actual terms 'compositionality' and 'function' until now. It should be clear, for example,'that a simple algebraic expression such as v = 2x + 4 satisfies the definition of 'composi-tional function' given above in that the numerical value of y is fully determined by whatever numerical value is assigned to x ( within a specified range), on the one hand, and by the arithmetical operations of addition and multiplication, on the other. The lexemes used so far to illustrate the principles of compo-ncntial analysis can all be seen as property-denoting words. They are comparable with what logicians call one-place predicates:expressions which have one place to be filled, as it were, in order for them to be used in a well-formed proposition. For example, if 'John' is associated with the one-place predicate 'boy' (by means of what is traditionally called the copula: in English, the verb 'be', in the appropriate tense) and if the seman-tically empty indefinite article a is added before the form boy (so that 'boy' in the composite form a boy is the complement of the verb 'be'), the result is a simple declarative sentence which can be used to express the proposition "John is a boy". (For simplicity, I have omitted many details that will be taken up later.) Other words, notably transitive verbs (e.g., 'hit', 'kill'), most prepositions, and nouns such as 'father', 'mother', etc. are two-place relational predicates: they denote the relations that hold 4.2 Componential analysis 113 between the two entities referred to by the expressions that fill the two places (or alternatively, as in the case of 'father', 'mother', etc., the set of entities that can be referred to by the set of expressions that fill one of the places). This means that their decomposition must take account of the directionality of the relations. For example, (6) "father" = parent & male is inadequate in that it does not make explicit the fact that fatherhood is a two-place (or two-term) relation or represent its directionality. It may be expanded by adding variables in the appropriate places: (7) "father" = (x,y) parent & (x) male, which expresses the fact that parenthood (and therefore fatherhood) is a relation with two places filled (x,j) and that (in all cases of fatherhood - on the assumption that the variables are taken to be universally quantified) x is the parent of y and x is male. This not only makes clear the directionality of the relatiqn (in the relative order of the variables x andj). It also tells us that it is the sex of x, not of y, that is relevant. There are other complications. Most important of all is the necessity of introducing in the representation of the sense of certain lexemes a hierarchical structure which reflects the syntactic structure of the prepositional content of sentences. For example, "give" is more or less plausibly analysed as one two-place structure (y,z) have, embedded within another two-place structure (x,*) cause, where the asterisk indicates the place in which it is to be embedded: (8) (x, (y,z) have) cause. This may be read as meaning (the question of tense being left on one side) "x causes y to have 2". And "kill" can be analysed, similarly, as a one-place structure embedded within,the same causative two-place structure: (9) (x, (y) die) cause, 114 The structural approach which may be read as'meaning "x causes y to die". Representations of this kind presuppose a much more powerful system of formalization than the set-theoretic operations sufficient, in principle, for the examples used earlier in this section. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the compositionality of more complex examples such as "give" and "kill" can be formalized. Various alternative proposals have been made in recent years, notably by linguists working within the framework of various kinds of generative grammar. 4.3 THE EMPIRICAL BASIS FOR COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS To say that componential analysis can be formalized is a quite different matter from saying that it is theoretically interesting or in conformity with the facts as they present themselves to us in real life. Theoretical motivation and empirical validity raise questions of a different order from those relating to formalization. The theoretical motivation for componential analysis is clear enough. It provides linguists, in principle, with a systematic and economical means of representing the sense-relations that hold among lexemes in particular languages and, on the assumption that the components are universal, across languages. But much of this theoretical motivation is undermined when one looks more carefully at particular analyses. First of all, there is the problem of deciding which of the two senses of 'basic' discussed in the previous chapter should determine the selection of the putative atomic universal components. There is no reason to believe that what is basic in the sense of being maximally general is also basic in the day-to-day thinking of most users of a language. Moreover, it can be demonstrated that, if one always extracts those components which can be identified in the largest number of lexemes, one will frequently end up with a less economical and less systematic analysis for particular lexemes than would be the case if one analysed each lexeme on its own terms. As for the empirical validity of componential analysis, it is not difficult to show that this is more apparent than real. For 4.3 The empirical basis for componential analysis 115 example, the analysis of "boy", "girl" and "child" (i.e., of the sense of the English words 'boy', 'girl' and 'child') given in the preceding section tells us that all boys and girls are children. But this is not true: the proposition expressed by sayingi' John is a boy and Jane is a girl

|