Starting an Induction Motor

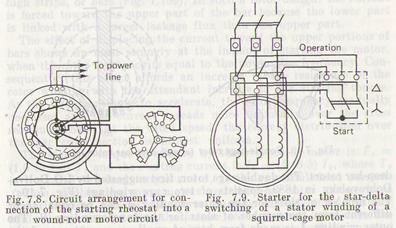

When started on full-line voltage, an induction motor draws up an increased current that can be a few times the rated load current flowing in the stator and rotor windings. The thing is that at standstill, the rotating magnetic field threads the rotor winding at a high rate equal to its rotational speed and induces a large emf in this winding. The emf produces a high current in the rotor circuit, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the stator current. As the rotor gains speed, the slip goes down and causes the rotor emf and current to drop off with the result that the stator current falls accordingly. A high starting current is objectionable both for the motor and for the source that supplies it. At frequent starts, the high starting current heavily heats up the motor winding and can lead to a premature aging of the insulation. Large starting currents are responsible for a dip in voltage of the power line, which affects the operation of other machines run off the same power line. Therefore, "across-the-line" starting is permissible only if the motor power is much lower than the power of the voltage source. If the motor power is comparable with the power of the source, it is necessary to reduce the current supplied to the motor at starting. Wound-rotor motors exhibit good starting characteristics. To reduce the starting torque, a wound-rotor motor is started on full-line voltage but with an external resistor called the starter rheostat connected to the rotor winding (Fig. 7.8). The resistor reduces the-rotor current, for which reason both the stator current and the current drawn from the line become low in magnitude. This increases the active component of the rotor current and thus allows the motor to deliver a high starting torque at a light line current. A starter rheostat has a few contacts by which it is possible to reduce in steps the resistance introduced into the rotor circuit. As the motor accelerates and picks up speed, the rheostat is completely brought out of the circuit by short-circuiting it and, hence, the rotor winding. When the rotor runs at the rated speed, the slip is small and the emf induced in the rotor winding is insignificant. And so, there is no need for the added resistance after the motor has started. Starter rheostats operate for a short time that is sufficient to enable the motor to accelerate and are designed for a short-time action. A rheostat will become inoperative if it is left connected in the circuit for a long time. A squirrel-cage motor whose power is low in comparison with the power of the line is usually designed for across-the-line starting.

A high-power motor, however, is started on reduced voltage by connecting it to the line through a compensator (stepdown autotrans-former starter) or a starting reactor. When the motor accelerates nearly to full speed, the starting lever is thrown to the running position, thereby transferring the motor to full voltage. A disadvantage of this method of starting is a sharp reduction in the starting torque. A decrease of the starting current by a factor of N requires a proportionate reduction in the line voltage. The starting torque then decreases in proportion to the square of the voltage impressed on the motor, namely, by a factor of N2. Since the starting torque is small, the motor should carry no load or a slight load at starting. The star-delta switching of the stator winding is quite a common method of.starting (Fig. 7.9). The starter illustrated in the figure connects the stator winding in star to allow the motor to come to speed and then transfers it to delta for running. The star-delta starting reduces the starting current drawn by the motor to one-third its full value. This method of starting is applicable for a motor which normally runs with its startor winding closed on delta.

|